Earlier this year, news broke that bottled water contains more plastic than originally thought.

The report was the latest from studies on microplastics, or miniscule fragments of plastic, that have been found all over the world: on Mt. Everest and in Antarctica, in coral reefs and the Great Lakes, in teabags, oysters, and our own bodies.

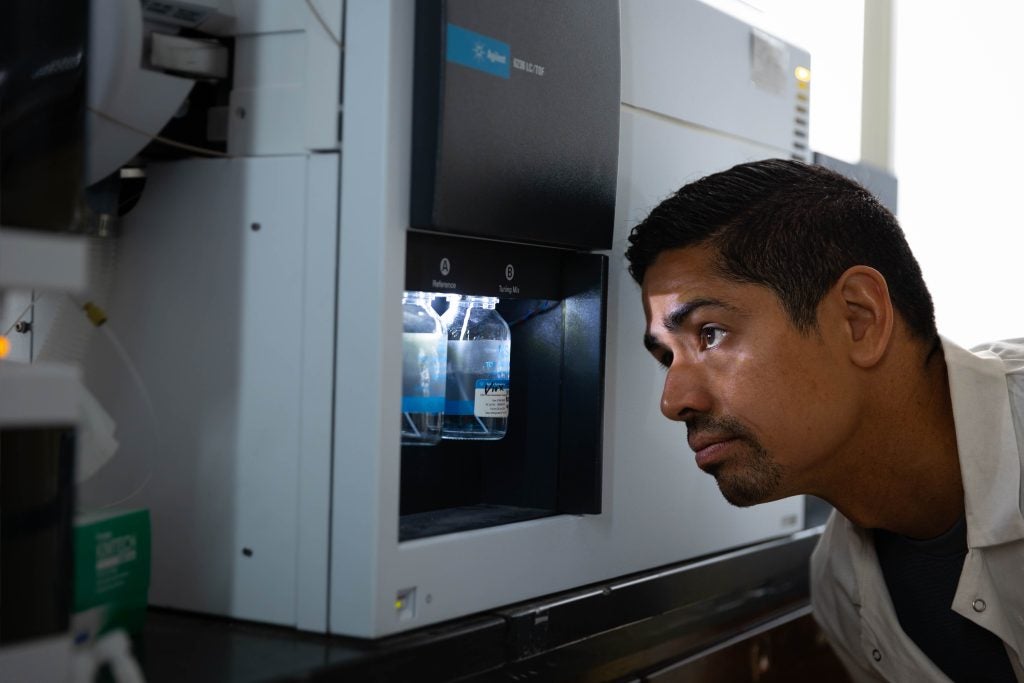

Scientists know microplastics are pervasive. But they don’t have a universal standard in this emerging field to identify or measure these tiny particles, says YuYe J. Tong, a chemistry professor and director of the Environmental Metrology & Policy Program (EMAP). And some of these particles are so tiny – 1,000 times smaller than a strand of hair – that measuring them, let alone standardizing the measurements, is a challenge. Without a universal standard, scientists can’t establish the extent of the issue or the level of exposure to humans to inform guidelines and policy.

“How are you going to manage or eliminate it? You have to measure it first,” Tong said. “That’s what we’re training students to do. We teach students to understand science and how science can be part of policymaking.

I’m a true believer that you can only maximize the societal impact of science and technology with the right support of developing and implementing soundest policy.”

In a year-long project, students and faculty members from EMAP and the Earth Commons are dipping into rivers and using a highly specialized infrared microscope to detect and measure just how much microplastic is there — and where it’s coming from.

Learning in the River

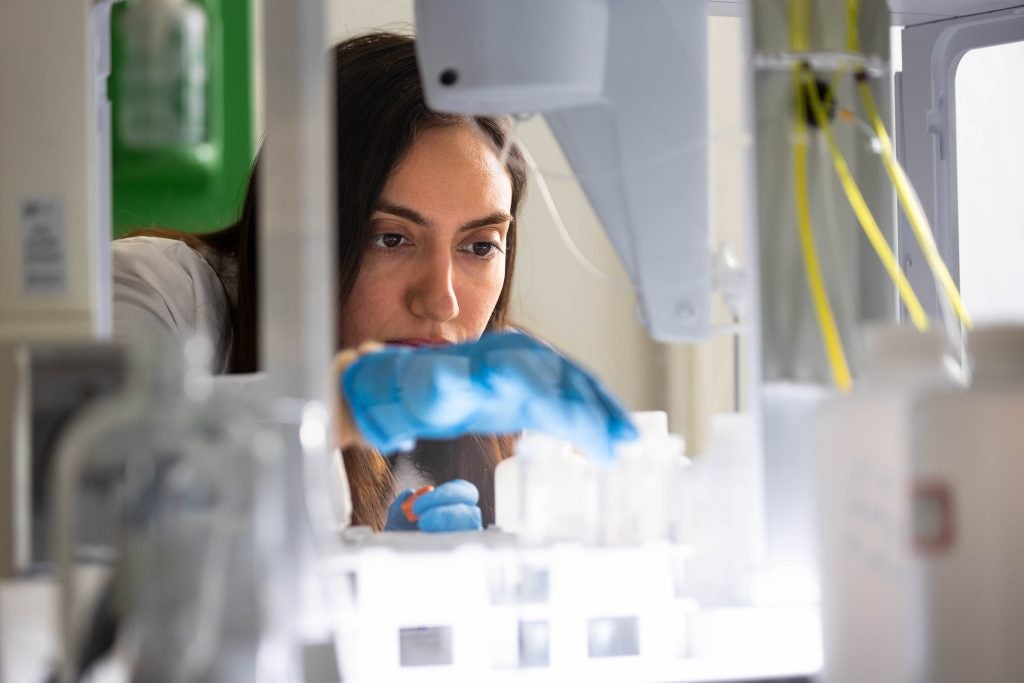

In December, Andrew Wilps (G’24) waded into the cold waters of the Anacostia River. He held out a jar in front of him, careful not to get any plastic residue from his rubber boots into the sample.

With his classmates, Ava Hanson (G’24) and Alexis Lashbaugh (G’24), they filled three jars with water and measured the river’s salinity, temperature and other parameters to record the water quality. They drove to four other sites that day, up and down the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers, before delivering the samples safely to a fridge in EMAP’s lab.

Their field work was part of a year-long study led by Jesse Meiller, an associate teaching professor in the Earth Commons Institute who specializes in microplastics, in partnership with Dejun Chen, an assistant teaching professor in EMAP, and colleagues from American University.

This research contributes in part to a grant funded by the Water Resources Research Institute, which has the team looking at how population density and land use impact the variety and abundance of microplastics that are found in different waterways around DC, assessing variations upstream and downstream of the city.

“I am really curious about where these pollutants are coming from and are they connected,” Meiller said. “We know the majority of the plastic that ends up in the ocean originates on land. And then it moves to the rivers. It makes a lot of sense to focus on looking at the rivers as major pathways of microplastics to oceans.”