Title: Study Will Lead to Human Trial of Cancer Drug to Prevent Parkinson’s

A Georgetown study in animals finds that small doses of a leukemia drug halt the production of harmful brain proteins that are linked to Parkinson’s and other brain degenerative diseases.

MAY 30, 2013TINY DOSES OF Adrug used for leukemia has halted toxic brain proteins linked to Parkinson’s disease in a newGeorgetown University Medical Centerstudy using animal models.

The senior investigator of the study is planning a clinical trial in humans to study the effects of the drug, called nilotinib.

The study, recently published online inHuman Molecular Genetics, provides a novel strategy in treating neurodegenerative diseases that feature abnormal buildup of such proteins involved in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia, Huntington disease and Lewy body dementia, among others.

BRAIN GARBAGE DISPOSAL

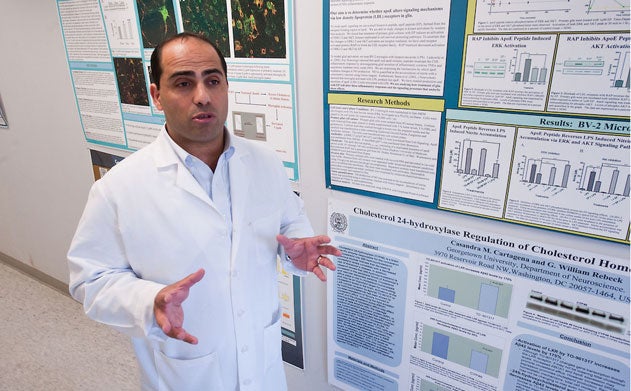

“This drug, in very low doses, turns on the garbage disposal machinery inside neurons to clear toxic proteins from the cell,” says the study’s senior investigator, neuroscientistCharbel E-H Moussa. “By clearing intracellular proteins, the drug prevents their accumulation in pathological inclusions called Lewy bodies and/or tangles, and also prevents protein secretion into the extracellular space between neurons, so proteins do not form toxic clumps or plaques in the brain.”

Moussa heads the Laboratory of Dementia and Parkinsonism at Georgetown.

When nilotinib is used to treat chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), it forces cancer cells into autophagy – a biological process that leads to the death of tumor cells in cancer.

“The doses used to treat CML are high enough that the drug pushes cells to chew up their own internal organelles, causing self-cannibalization and cell death,” Moussa says. “We reasoned that small doses – for these mice, an equivalent to 1 percent of the dose used in humans – would turn on just enough autophagy [cell degradation] in neurons that the cells would clear malfunctioning proteins, and nothing else.”

Moussa, who has long sought a way to force neurons to “clean up their garbage,” came up with the idea of using cancer drugs that push autophagy in tumors to help diseased brains.

“No one has tried anything like this before,” he notes.

ANOTHER POSSIBILITY

Moussa, and his two co-authors – Michaeline Hebron (G’12) and Irina Lonskaya, a postdoctoral researcher in Moussa’s lab – searched for cancer drugs that have the ability cross the blood-brain barrier.

They discovered two candidates – nilotinib and bosutinib, which is also approved to treat CML. While this study focuses on nilotinib, Moussa says that use of bosutinib is also beneficial.

The team also showed that movement and functionality in the treated mice were greatly improved, compared with untreated mice.

EARLY USE MOST BENEFICIAL?

For the therapy to be as successful as possible in patients, the agent would need to be used early on in neurodegenerative diseases, Moussa hypothesizes.

Moussa is planning a phase II clinical trial in participants who have been diagnosed with disorders that feature buildup of the protein alpha Synuclein. These disorders include Lewy body dementia, Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and multiple system atrophy (MSA).

The National Institutes of Health grant (NIA 30378) as well as Georgetown University funding supported the study.

Moussa is listed as an inventor on a provisional patent application to use nilotinib and bosutinib as a therapeutic approach in neurodegenerative diseases.