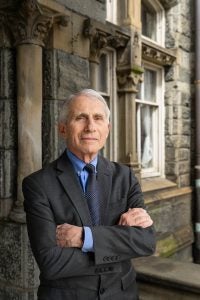

Dr. Anthony Fauci reflects on his long career in public service in a new memoir almost one year after joining the faculty at Georgetown.

The book, On Call: A Doctor’s Journey in Public Service, chronicles Fauci’s upbringing rooted in Jesuit education and his long career in public service, including 38 years as the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In his memoir, Fauci recounts how he navigated several public health crises from AIDS in the 1980s to COVID-19 in the 2020s, advising seven U.S. presidents and culminating in his service as the chief medical advisor to President Joe Biden.

For Fauci, the memoir has been a decades-long project he first envisioned while advising former President Bill Clinton. Since then, he’s taken copious notes on his experiences, collecting bits of wisdom to pass down to the next generation of public servants.

“My situation was unique because I lived through it personally, and I thought that would be a valuable experience to share generally, not only in the United States but globally,” he said. “No one has had the experience in global health of being able to advise seven presidents with the bookends of my career being HIV/AIDS in the early years and COVID at the end of my career.”

Now a Distinguished University Professor with appointments in the School of Medicine and the McCourt School of Public Policy, Fauci has spent much of the last year engaging with students across the university. He has loved interacting with students through lectures, fireside chats and casual encounters on Healy Lawn and Yates Field House, he said.

At Georgetown, he feels right at home.

“I just feel so much at home [here] … and that’s a really good feeling,” Fauci said. “Sometimes, when you come to a new place, you feel like an outsider. I don’t feel at all like an outsider. I feel like it’s a place where I belong.”

As Fauci celebrates the launch of his memoir and almost one year at Georgetown, we asked him how public service has evolved over time, what advice he’d give to aspiring public servants and how his own life has changed since coming to Georgetown.

What is the main message of the book that you want readers to take away?

The one I think will come to the reader as they read it is how extraordinarily gratifying and fulfilling a career in public service is, but also how challenging it could be because you really face unexpected challenges. A lot of times when I talk, I say one of the great lessons is to expect the unexpected, which, if you read the book, you see how many things popped up in front of me that were not anticipated, nor were they planned for. Everything from the direction of my career to the outbreaks that I had the opportunity to address.

You’ve spoken about how the Jesuit ideals of service and care for others motivated you throughout your career. How do those values animate your role at Georgetown?

The reason I picked Georgetown among many reasons was it is reflective of the principles that I’ve lived by and that I was trained in through my own experience in high school and in college about service for others, founded in a high degree of integrity, honesty and empathy. That’s the spirit that I see at Georgetown. So to me, Georgetown would be a perfect fit as the culmination of my long career.

How has your day-to-day life changed since leaving public service?

During the early years of HIV, the intensity of when I developed the PEPFAR [U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief] program with George W. Bush, and obviously during the very intensive years of COVID … I really pushed myself to the limit. I mean chronically, not just one weekend or one week. I was chronically sleep-deprived for decades. I worked 16 hours a day.

I was very fortunate that I had my wife, Dr. Christine Grady, who by the way is a double Hoya. … She’s an amazingly supportive person, so I don’t think I’d be able to have done that without her support. But it was really just wearing yourself into the ground every day, accomplishing a lot, of course. We saved millions of lives, and I’m very proud of that, not only with the development of the drugs for HIV, but for the development of the PEPFAR program and the development of the vaccine for COVID. But it was a grueling schedule.

Since I left the NIH and joined Georgetown, I think I’m working almost as hard in all the things I’m doing, working to write the book, working to do all the things I do. The only difference is I don’t feel like I’m chronically sleep-deprived. I now get seven hours of sleep a night, whereas before I used to get four to five hours of sleep a night.

How has public service changed throughout your career, and what are the opportunities and challenges facing young people interested in becoming public servants?

The opportunities are probably broader now because we operate much more on a global level. Fifty years ago, people were focusing mostly on somewhat provincial issues that relate only to their immediate environment and the country they’re in. Right now, we live in a global society, so public service has so many more opportunities.

The challenge is what I mention in the book that, unfortunately, we’re living in an era of a profoundly divided society. We’ve always had appropriate and understandable diversity of opinion and diversity of ideology. People in the center, center-left, far left, center-right, far right. That’s fine. Diversity allows for a healthy and vibrant democracy. But when that diversity becomes profound divisiveness, that really interferes with so many things that you’d like to do. I think divisiveness in society is one of the great challenges that the younger generation is going to face in whatever it is that you want to do.

Why is inspiring the next generation of public health leaders and public servants important to you?

Public health is one of the most important issues of the human race. Without health, so many other things fall by the wayside that don’t function as well. We have a responsibility as a society to promote public health, and the individuals who get involved in that are individuals who have taken up and assumed a considerable degree of important responsibility.

I think the book might help at least somewhat in getting people who read it to realize how gratifying an experience of being a public health person is. Or even if it’s not public health, at least public service. Remember, the title of the book is “A Doctor’s Journey in Public Service.” So you don’t have to be a doctor or a scientist to do public service. You can incorporate public service into any career path you choose.

What advice would you give to someone considering a career in public service?

It’s less advice than it is an observation, and my observation is that having a career in public service is such a gratifying feeling. When you go through life as I have through so many decades, you have a lot of different experiences with a lot of different people, and there are so many people I know who do productive things but don’t get the feeling that they’ve actually contributed to society.

They may have made a lot of money. They may have had a lot of fun, but when they start to ask themselves, “What have I contributed to society? Have I made the world a better place?” Sometimes people realize they have not, and that’s not a great feeling.

But the people I know, myself included, who’ve devoted their lives to public service, when you take a breath and think about what you’ve done, it’s a very fulfilling and gratifying feeling. … If you want to get a good feeling about yourself and you have some inclination to do public service, I would strongly recommend you seriously consider it because it might turn out to be the fulfillment that you’re looking for in your life.