Artistic swimming begins this week at the 2024 Paris Olympics with a few milestones in its wake.

It’s the first year the U.S. artistic swimming team, formerly known as synchronized swimming, is competing in the team event at the Olympics in 16 years — a comeback after Americans dominated the sport for decades.

It’s the first Olympiad that men are allowed to compete in the sport’s team event, although no countries will be sending any male competitors this year.

And it’s the 40th anniversary of the sport’s official entry into the Olympics — a relative latecomer after early forms of artistic swimming were performed in flooded Roman amphitheaters and glass tanks in Victorian England.

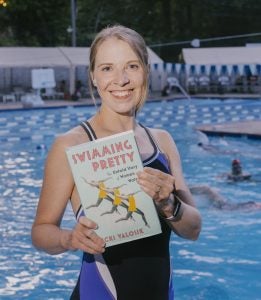

Vicki Valosik, an adjunct writing instructor in Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service and editorial director for Georgetown’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, uncovers much of this aquatic history in her new book, Swimming Pretty: The Untold Story of Women in Water, which chronicles women’s rise in all forms of swimming, including synchronized.

For Valosik, her interest in synchronized swimming’s history began, appropriately, in the pool.

She took up the sport herself more than a dozen years ago, and was practicing for her first competition in 2011 when her teammates told her to take off her goggles, per the norms of the sport. She was surprised, given that swimmers in other sports wear goggles, but she took them off and dove underwater. She remembers feeling keenly aware as she spun and swam that she couldn’t breathe or see.

“Clearly it’s an athletic and difficult sport,” she said, “but there’s this performance aspect of it as well, such as not wearing goggles simply because it doesn’t look as good. I was curious about that tension as I was looking into the history and was struck by seeing this sport versus spectacle conflict pop up over and over through the decades.”

That tension between athleticism and performance is the question Valosik continued to explore as she dug through archives at the International Swimming Hall of Fame and pored through physical education journals and the scrapbooks and personal effects of early Olympians and aquatic performers of the carnival world. She interviewed swimmers who went on State Department missions to spread the sport internationally, former coaches, and top athletes and leaders in artistic swimming today.

Valosik hopes to share her research with the Georgetown community this fall. In the meantime, dive into the sport’s surprising history, its Cold War-era battle for Olympic acceptance, and what to look for in the pool at this year’s Summer Games.

Synchronized swimming looks so effortless, but it takes so much strength underneath the water. What’s hard about the sport, and what strengths do you need to be successful at it?

The biggest things are endurance and lung capacity. Athletes are conducting incredibly difficult maneuvers upside down in the water. At the Olympics, they spend more than half of the routine underwater. As a routine goes on and the athletes are breathing faster and their heart rates are elevated, these moves become increasingly difficult. Imagine you’re running a sprint and then suddenly you have to hold your breath. That would be so much harder, right?

At the same time, the swimmers are often changing patterns, shifting spatially and in relationship to one another, while upside down in the water. On top of that, they are traveling all over the pool. Then, of course, there’s matching everyone perfectly in the water, an element that doesn’t lend itself to sharp and precise movements.

And all of this takes place in deep water. When you see the swimmers catapulting someone out of the water, it’s easy to forget they’re not touching the bottom of the pool. They are kicking as hard as they can to create enough tension against the water to propel not just themselves above the surface, but also the body weight of the people they’re supporting and lifting. It requires an incredible amount of strength.

What made you want to write a book about synchronized swimming?

I was fascinated to discover that the sport’s development was deeply connected to important social currents over the years and specifically to women’s physical empowerment.

For example, Annette Kellerman became a vaudeville and silent film star for her aquatic performances, which escalated to become increasingly dangerous in her movies. She did things like swim with her hands tied behind her back through rapids. She swam with alligators. She dove from a hundred-foot-tower into the ocean, barely missing the rocks surrounding the tower’s base. Her movie, A Daughter of the Gods, came out in 1916 when the agitation for women’s suffrage was building and reviewers of her movies made connections between her physical daring and women’s political enfranchisement. Several wrote things like, ‘Anybody who thinks women aren’t as strong as men and therefore shouldn’t have the right to vote need to go watch Annette Kellerman.’

As I was discovering these interesting connections between swimming performance and other important developments for women, such as suffrage, the development of lifesaving, the growth of physical education and how synchronized swimming and its evolution was tied to these things, I realized it was a fascinating story — and one that hadn’t been told.

What were you surprised to learn about the history of women’s swimming?

I was surprised at how hard women had to fight, over and over, to be taken seriously as athletes. In the Victorian era, women had to fight to simply get to swim and do it in clothing that was not dangerous in the water. Then they had to fight to get into the world of sports at a time when people believed that women should conserve their energy to have children and be good mothers, and that sports would make women masculine.

At the same time, it was also surprising to discover how differently female swimmers, who were seen as the glamour girls of sport, were treated in comparison to other female athletes. Women in the early 20th century were not supposed to exert themselves in public, but for swimmers, the water hides much of their physical effort. Swimming was considered a beautifying sport that didn’t create big, knotty muscles and was considered aesthetic and pretty to watch.

As a result of being seen as an appropriately feminine activity, swimming became the first national competitive sport for women in 1916. America’s first real women’s Olympic team were the female swimmers and divers who competed in the 1920 Olympics. These swimming stars parted the waves for other women athletes, and once the doors to the world of sport opened, women’s athletics really took off.

Was there a time when women’s swimming was taken more seriously than synchronized swimming?

As early as the twenties, when the American women dominated Olympic swimming and diving, and Gertrude Ederle became the first woman to swim across the English Channel (and doing it faster than the five men who had swam it before her), people were like, ‘Wow, this is a sport women are good at.’ Women in aquatic sports were some of the first to be respected as real athletes.

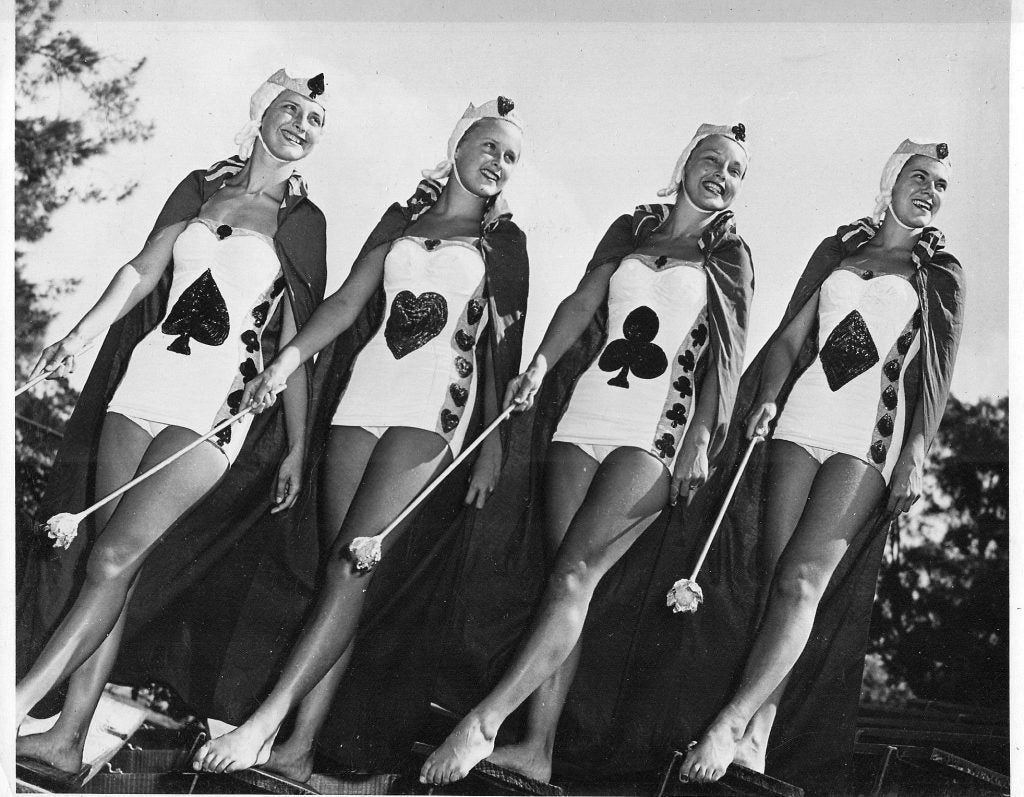

On the other hand, synchronized swimming, which became a competitive sport in 1939, struggled for many years to be taken seriously. This was largely because it remained associated with the performative styles of aquatics it had evolved from like Red Cross water pageants. These plays, which featured costumes, dialogue and swimming scenes, were used to spread information about water safety and teach the public swimming and lifesaving skills.

Synchronized swimming became a popular form of professional entertainment as well, with spectacular water shows like Billy Rose’s Aquacades and Esther Williams’ MGM ‘aquamusicals’ all featuring dazzling and glamorous water ballets. Williams soared to fame at the same time that competitive synchronized swimming was taking off, which permanently linked the sport — at least in the public imagination — with the world of show business. It became a constant quest over the fifties, sixties and seventies by the synchronized swimming community to distance itself from these entertainment roots and become increasingly aligned with the world of sport.

Why did it take so long for synchronized swimming to become an official Olympic sport in 1984?

There was a lot of pageantry involved in the early years of synchronized swimming, and it took a long time to shake that image, even as the sport grew increasingly athletic and technical over the years. Avery Brundage, the longtime president of the International Olympic Committee, called synchronized swimming ‘aquatic vaudeville’ and repeatedly refused proposals to bring synchro’s Olympic acceptance up for a vote.

But in the post Title IX era, there was a push for more women’s sports in the U.S., which spread to the Olympic level. Synchronized swimming and rhythmic gymnastics, both of which were women-only sports at the international level at the time, were voted in together for the 1984 Olympics.

Even after Olympic acceptance, the sport still struggled to be taken seriously, especially by the media. After the 1984 Olympics, Saturday Night Live aired its now-famous skit with Martin Short and Harry Shearer playing male Olympic hopeful synchronized swimmers — despite the fact that they could barely swim.

But in the early nineties, U.S. Synchronized Swimming did something clever. They realized that most people had no idea how difficult the sport was, so they issued a ‘media challenge,’ inviting any willing journalist to join one of the country’s top teams for a practice in the pool. A few took them up on it, including the famous humor columnist Dave Barry. Without fail, these writers reported on how surprised they were at the incredible athleticism and difficulty of the sport and their newfound respect for its athletes. So to actually have journalists who had been making fun of synchronized swimming come and try it and be completely changed, it was a successful campaign.

Are there any countries to watch or major rising stars that you’re rooting for in this Olympics?

It’s exciting to have an American team to cheer for again, since the last time the U.S. qualified for the team event was in 2008.

After falling behind other countries and failing to qualify for the team event in 16 years, the U.S. national team has been making a huge comeback in recent years and climbing up in the international rankings. Also, new rules that aim for greater objectivity in scoring are being used at the Olympics for the first time this year.

Between the U.S. comeback and the overhaul in the rules, combined with the fact that Russia — which has won every Olympic artistic swimming medal of the 21st century — has been barred this year from the Olympic team events, we could see some exciting changes on the podium in Paris!

Your book mentions that there were geopolitical forces at play with Russia. Did Russia try to develop a team in response to America owning the sport for so long?

Absolutely. In the seventies, the U.S. was the dominant country in synchronized swimming while the Soviet Union didn’t have a very developed program. As a result, they were opposed to adding synchro, a sport America would win, at the World Aquatic Championships or the Olympics. When the addition of synchro came up for a vote at the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, it was voted down, largely due to Soviet opposition. In the end, it wouldn’t have mattered since the U.S. led a boycott of the 1980 Olympics because of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Before the 1984 Olympics, rhythmic gymnastics, which originated in Russia, was put forward as a new event. It was accepted alongside synchronized swimming for the Los Angeles games.

The U.S. continued to be the dominant country for synchronized swimming for the remainder of the century, and in 1996, when the team routine debuted, America got a perfect score. But then the entire Olympic team retired and the athletes taking their place didn’t have the same level of competitive experience. Russia, meanwhile, had been working hard to build its national program and in 2000, catapulted to first place. The Russian team has dominated the sport ever since, pushing the bar and elevating it to ever greater levels of athleticism.

You mentioned women having to fight to be taken seriously in this sport every step of the way. Does it make you look at your own practice of synchronized swimming differently from when you first began, knowing what it took for women to get to this point?

It makes me grateful for what so many women went through — not just to make synchronized swimming a respected sport — but so that women can even be athletes in the first place. Because of these female pioneers of the water, the majority of American women today know how to swim and also know that they can play any sport they want.

My research has also given me a deeper appreciation for how liberating sports have been for women over the years — how much it has meant to women, especially of earlier generations who had to navigate such strict gender norms, to learn that they can do these incredibly difficult physical things, and the empowerment that would have come with that.