Title: Blacks and Jews in America Course Examines Divisions, Shared Hopes Between Groups

A course on Blacks and Jews in America taught by Jewish civilization scholar Jacques Berlinerblau and theology, government and African American studies professor Terrence Johnson examines relationships, hopes and divisions between the two groups.

Jacques Berlinerblau

October 27, 2017 – While Omoyele Okunola (C’20) and Kate Lambroza (C’18) grew up aware of the effects of racism and anti-Semitism on African Americans and Jews, they didn’t deeply explore the relationship between the groups before taking a course on the subject this semester.

Terrence Johnson, associate professor of theology and government, and Jacques Berlinerblau, professor in and director of the university’s Center for Jewish Civilization (CJC) in the School of Foreign Service, are now in their second year of teaching a course, titled “Blacks and Jews in America.”

The course examines the confluence and divergence of ways in which African Americans and Jews have pursued their religious and cultural identities.

Systematically Oppressed

“Here are two groups who were legally and systematically oppressed by white America and the Nazi regime in Germany,” says Okunola, a sophomore American studies and government major from New York. “These two groups were exploited mentally, physically and sexually. Between slavery and the Holocaust, millions of people lost their lives because of their race or religion.”

Lambroza, a senior government major who also lives in New York, became familiar with anti-Semitism at an early age. Originally from Surrey, England, she moved with her parents to Boston at age 14.

At age 11, her uncle shared a story about traveling in the Southern part of the United States and meeting a mechanic who facetiously asked him whether there were “any Jews left” in the world after the Holocaust.

“It was the first time I thought about how there were still people around who thought like that, who didn’t like Jews,” she says.

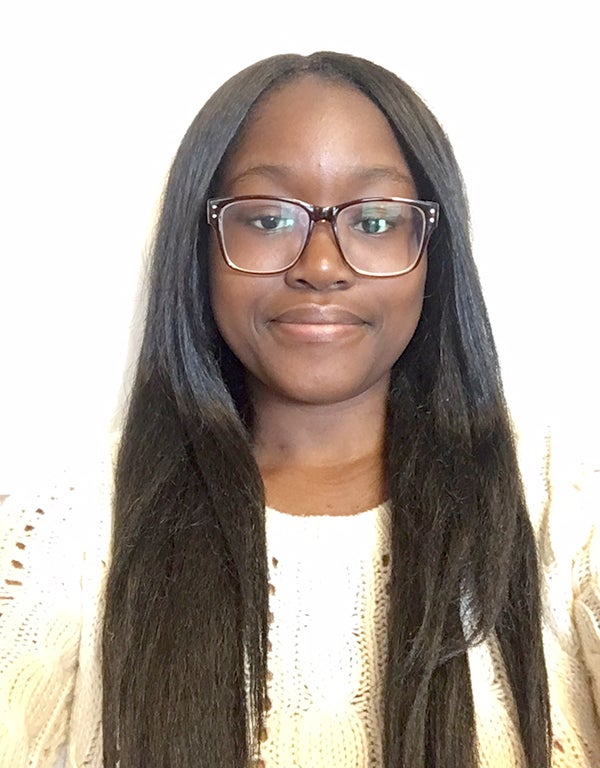

Omoyele Okunola

The Fracture

“The class visits the long and complicated history of blacks and Jews, which is more than a century old at this point,” Berlinerblau explains. “The assumption has been, from about 1967 or 1968 to the present, that what was once a pretty solid alliance sort of fractured.”

Though the course focuses on this “fractured” period, Johnson thinks the relationship between the two groups began to unravel sooner than the late 1960s.

“I would argue that it’s always been kind of a tenuous relationship, in part, because Jews were often in positions of authority when dealing with African Americans,” Johnson explains. “At the same time, they were able to work together in some very interesting ways.”

Critiquing Israel

The two groups worked side by side, for example, in establishing the NAACP, and both groups held leadership positions in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the prominent civil rights movement organization.

“When SNCC decided to critique Israel in 1967 and 1968 over its treatment of Palestinians, that created huge turmoil,” Johnson says. “SNCC also was beginning to rethink the role of whites in the organization and whether or not they should have leadership positions.

“If you look at every other ethnic group, people have control over their organizations, and the thought at the time was that ‘We don’t, and what does that say as we are trying to empower people?’ he explains.

Religion and Politics

Johnson says American democracy cannot be studied without looking at the role religion has played in shaping the nation’s perceptions of African Americans and Jews.

“As we look at the reasons why blacks have faced racism and why Jews have faced anti-Semitism, we will see signs of a religion and how religion intertwines with politics,” he says.

Lambroza was born to a Jewish father from Israel and an Irish, non-practicing Catholic mother.

She identifies as Jewish and credits the CJC with helping her get in touch with Judaism, but says her knowledge of the African American experience was limited before the course.

Kate Lambroza

“I did not grow up around a lot of black people,” she explains. “I had never taken a class that had African Americans as the center of it, and I felt like it was a huge part of my knowledge that I was missing.”

America as Egypt?

In contrast, Okunola, a Muslim, grew up in New York’s Bronx borough around diverse groups of friends and classmates.

“Since I am from New York, I’m used to being around black and Jewish individuals,” she says. “I was always fascinated by how Jewish Americans had been able to thrive in this country given their history … and how that seems so different from the black experience.”

The course examines the Bible and the Torah’s Book of Exodus, the story of how Israelites left slavery in Egypt through the strength of God.

“There are so many different interpretations of the same text and how the story of Exodus … can be tied to slavery in this country,” says Okunola, “and how African Americans today are unsure whether America is Egypt or if African Americans would ever obtain something like Israel for Jews.”

Revisiting Civil Rights Era

The professors opened the first class with something related to both racism and anti-Semitism – a viewing of the Vice News Tonight’s “Charlottesville: Race and Terror.”

In the video, white supremacists attending this past summer’s well-publicized August rally in Virginia talked openly about violence against blacks and Jews and chanted Nazi slogans.

Lambroza says watching the footage in class felt like an “out-of-body experience.”

“I could feel that sense of anxiety fear and shock,” she said. “I was literally on the verge of tears watching it because it is so violent and so extreme.”

“This is a real neon-light-blinking reason that blacks and Jews on the individual and institutional levels should start maybe revisiting the work they did in the great civil rights era,” Berlinerblau says. “These are two groups that like to talk a lot. Sometimes it’s beautiful and sometimes it’s not, but it’s always interesting.