Title: Georgetown Shares Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation Report, Racial Justice Steps

Georgetown University President John J. DeGioia announces next steps in the university’s ongoing process to acknowledge and respond to its historical ties to the institution of slavery.

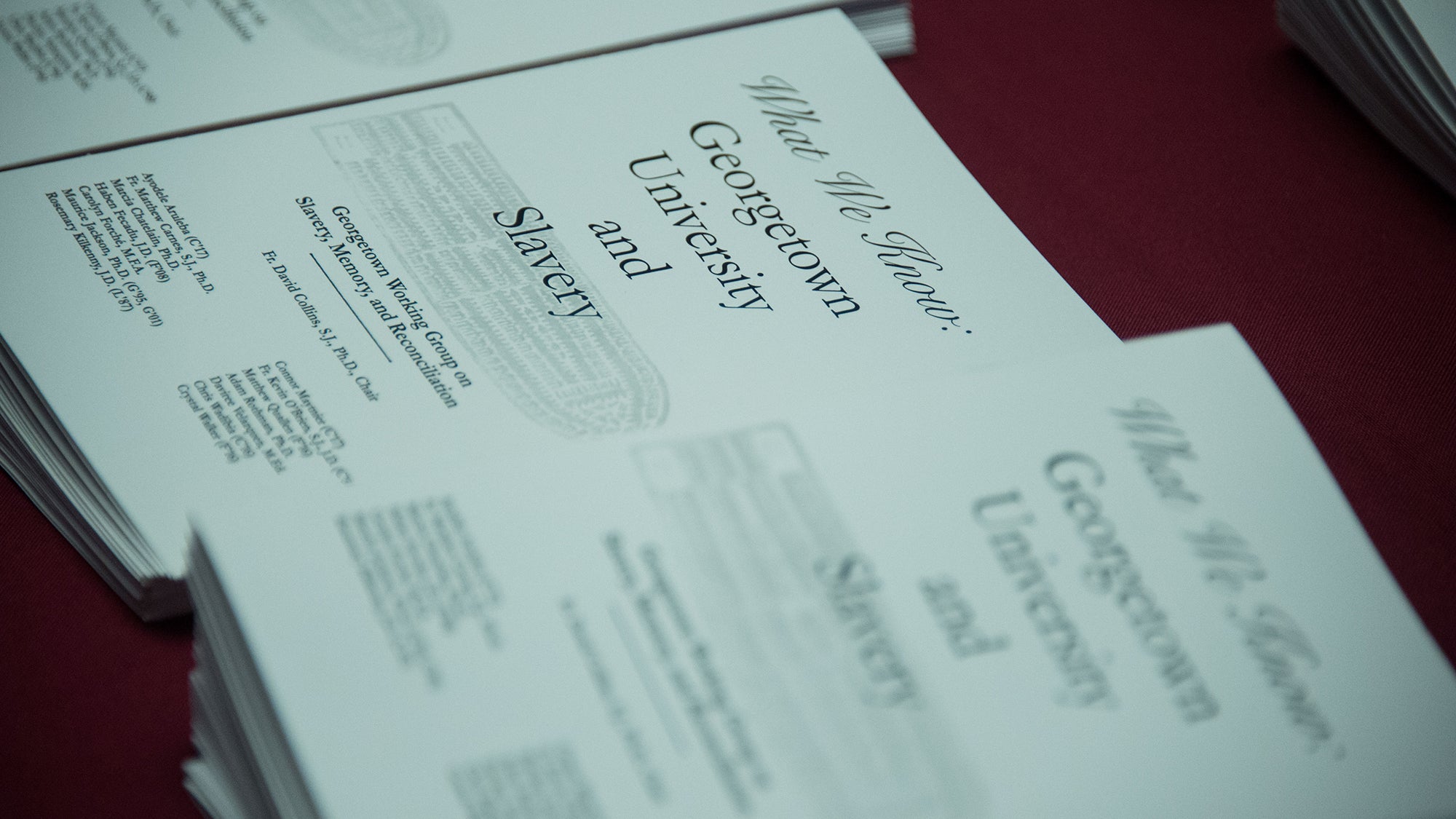

In sharing the report and recommendations of the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation, DeGioia said that the university will engage directly with descendants of slaves and with members of the Georgetown community in this ongoing effort.

This will include soliciting feedback, determining priorities for the work going forward, and creating processes and structures to enable that work.

The university intends to engage descendants both on campus and in the cities and communities where they live.

In September 2015, DeGioia convened and charged the Working Group, comprising faculty, students, alumni and staff and chaired by David Collins, S.J., to make recommendations on how best to acknowledge and recognize the university’s history as it relates to slavery; examine and interpret the history of certain sites on our campus; and convene events and opportunities for dialogue.

Part of this history includes the 1838 sale of 272 enslaved people who worked on Jesuit plantations in southern Maryland. Proceeds of the sale went to the Maryland Province of Jesuits and were used to pay off debts at Georgetown.

“I am grateful to the many members of our community who have thoughtfully and respectfully contributed their perspectives and shared their insights,” DeGioia writes in a letter prefacing the report. “I look forward to continuing to work together in an intentional effort to engage these recommendations and move forward toward justice and truth.”

Engaging Our History

“The most appropriate ways for us to redress the participation of our predecessors in the institution of slavery is to address the manifestations of the legacy of slavery in our time,” says DeGioia, who met over the summer with descendants in New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Maringouin, Louisiana, as well as Spokane, Washington.

Since the 16-member Working Group began its work last September, it has created a new digital archive of historical documents, conducted archival research on the enslaved persons, engaged descendants, hosted community dialogues and a “Teach-In,” and provided grants to community members to host activities that engaged this history.

This past April the group held events in recognition of D.C. Emancipation Day, honoring the day – April 16, 1862 – when slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia.

Over the course of a dozen days, 15 events took place, featuring such guests as Kimberly Juanita Brown, author of The Repeating Body: Slavery’s Visual Resonance in the Contemporary and Columbia University historian Craig Steven Wilder, author of Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities, andEdward Baptist (F’92), a historian at Cornell University and author of The Half Has Not Been Told.

WORKING TOGETHER

“Being a part of the Working Group has been one of the most gratifying experiences of my professional life,” says history professor Marcia Chatelain, who spoke at this past December’s Teach-In, which was held to increase the community’s familiarity with the university’s history of slavery. “It allowed me to do things I already love to do: research the past, teaching people about the relevance of history … and making sure that different parts of the Georgetown community were always engaged …”

Members of the Working Group over the year included students, faculty from the government, history, and English departments, staff, alumni and faculty who are also members of the Jesuit community at Georgetown.

“There was a mutual respect and admiration for each other and for the unique roles that we play, whether we were students at Georgetown, whether we were administrators at Georgetown, whether we were faculty,” says Working Group member Rosemary Kilkenny (L’87), vice president for institutional equity and diversity. “We all had a unique role … the one commonality was that … we are all committed to Georgetown.”

Recommendations

David Collins, S.J., the group’s chair, says he hopes the legacy of the Working Group is that “our community can say soberly and sincerely [that] this is part of our history and we take responsibility for it.”

“As we join the Georgetown community we must understand that part of our history is this history of slaveholding and the slave trade,” he says. “And that opens our eyes to broader social issues that are still unhealed in our nation. History matters up to the present and into the future.”

Some of the recommendations of the Working Group include:

Naming Freedom Hall (once known as Mulledy Hall) as Isaac Hall, in honor of Isaac, the enslaved person whose name is the first mentioned in the documents of the 1838 sale

Naming Remembrance Hall (once known as McSherry Hall) as Anne Marie Becraft Hall in honor of Anne Marie Becraft, a free woman of color who founded a school for black girls in the neighborhood of Georgetown in 1827. She later joined the newly founded Oblate Sisters of Providence in Baltimore, the oldest active Roman Catholic sisterhood in the Americas established by women of African descent.

Offering an apology for the university’s historical relationship with slavery

Engaging with the descendant community in an active and sustained manner

Developing a public memorial to the enslaved to ensure their memory is honored and preserved

Actively pursuing research and teaching, establishing a new Institute for the Study of Slavery and Its Legacies at Georgetown

University Response

The report submitted by the Working Group marks the completion of their task, but it is just the beginning of the new work ahead for Georgetown as a community.

In a messageto the community today, DeGioia announced actions that the university will take to engage its history with slavery and engage with descendants in new ways:

Offering a Mass of Reconciliation in conjunction with the Archdiocese of Washington and the Society of Jesus in the United States, and engaging the Georgetown community in a “Journey of Reconciliation”

Naming the building Freedom Hall (once known as Mulledy Hall) as Isaac Hall and name the building Remembrance Hall (once known as McSherry Hall) as Anne Marie Becraft Hall

Engaging descendants and members of our community in developing a shared understanding, determining priorities, and creating processes and structures

Establishing a living and evolving memorial to the slaves from whom Georgetown benefitted and establishing a Working Group, including descendants of those slaves, to advise on its creation

Establishing the Institute for the Study of Slavery and Its Legacies at Georgetown to support the continued, active engagement with descendants, sustained research and other actions

Giving descendants the same consideration we give members of the Georgetown community in the admissions process

Strengthening Georgetown’s Library and its Special Collections to promote scholarship in the field of racial justice and deepen archival resources to support genealogical work

Working to identify new ways to enhance access and opportunity for those who wish to attend college and continue to support schools like Cristo Rey that seek to provide stronger pathways to higher education.

Renaming Buildings

This past November, upon the recommendation of the Working Group and approval of the board of directors, the university removed from two buildings on campus the names of Georgetown presidents Thomas Mulledy, S.J., and William McSherry, S.J., who had administered the 1838 sale.

Mulledy Hall and McSherry Hall were provisionally renamed Freedom Hall and Remembrance Hall, with the understanding that the Working Group would suggest permanent names following further dialogue and engagement with the community.

DeGioia accepted, and the Georgetown University Board of Directors has approved, the Working Group’s recommendation to permanently rename both buildings. Freedom Hall for Isaac, a 65-year-old enslaved person at the time of the 1838 sale.

In the documents of the sale, Isaac is listed with his children, Charles, his eldest son; Nelly, his daughter; and family members who may have been children or grandchildren: Henny, Juliaand Ruthy.

Remembrance Hall will be named for Anne Marie Becraft (1805-1833), a free African American woman who opened a school for young African American girls in the Georgetown neighborhood in the 1820s.

In 1831, she joined the Oblate Sisters of Providence in Baltimore, the oldest active Roman Catholic sisterhood in the Americas established by women of African descent and was known by the name of Sister Aloyons.

After soliciting input from the Georgetown community on possible names for the buildings, Anne Marie Becraft was suggested to the Working Group by an alumnus, Dmitriy Zakharov (F’09, G’09).

Critical Moment

“I hope the work of the Working Group teaches people that nothing bad happens when we’re honest about the past,” says Chatelain. “I think we’re in a critical moment in our country about race relations and about navigating the long-term consequences of inequality.”

Working Group member Ayodele Aruleba (C’17) says learning more about slavery at Georgetown and other universities “really pushed me to commit toward racial justice work.”

“I think every institution has some obligation to recognize this issue,” says member Eric Woods (B’91). “And because we have names and families and histories and can point directly to people and directly to their descendants today in a way that most institutions can’t. We were in a very special place with regard to how we deal with it.”

Sharing Knowledge

The Working Group conducted extensive archival research, which it has made available to the public in an accessible online format, the Georgetown Slavery Archive, and which informed the group’s report and its description of the history of slavery at Georgetown.

History professor Adam Rothman led the archival work, including the development of the Georgetown Slavery Archive. Matthew Quallen (F’16) and Chatelain also participated in the archival efforts.

“Often when people think about history, conversations can get overheated, a lot of misinformation flows around and people make snap judgments,” Rothman says of the Working Group experience. “But we’ve been about a different kind of process – thoughtful, informed, with respectful conversations from a wide variety of perspectives. I hope that what we’re doing has a lasting impact. That what we’re doing now to engage with this history will endure decades from now.”

Maurice Jackson (G’95, G’01), a member of the department of history and member of the Working Group, urges people to study the report and accompanying documents.

“This was a labor of sorrow and a labor of love,” he says. “It’s the time of truth. Not just truth and reconciliation. I don’t know if you can reconcile all of this. But we can use the truth to illuminate the past and also figure out how we can go forward and solve the problems of the future.”