Title: Mountain-Climbing and Surfing GU Physicist Writes Book

A Georgetown professor’s successful 12-year mission to be the first to climb every continent’s highest peak and surf every ocean has culminated in a book comparable to Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer and other adventure tales.

Georgetown’s Francis Slakey, co-director of the Program on Science in the Public Interest (SPI), embarked on a 12-year mission to be the first person to climb the highest mountains and surf all the oceans in the world.

A Georgetown professor’s successful 12-year mission to be the first to climb every continent’s highest peak and surf every ocean has culminated in a book comparable to Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer and other adventure tales.

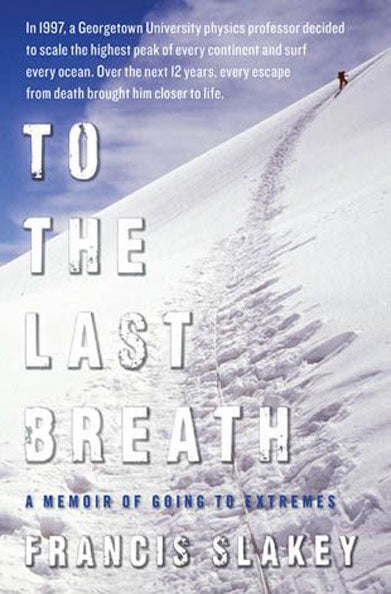

Francis Slakey’s To the Last Breath: A Story of Going to Extremes will be published in early May by Simon and Shuster, and chronicles his unique quest.

“I am out of balance,” the book begins, “I hang dangerously off center but I’m oblivious, until some dim awareness of the world shakes me awake.”

He goes on to describe a close call he and a friend had at 2,000 feet in the air on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park.

Life or Death Decisions

It was 1997, when Slakey was 37, that he decided to set a goal that even experienced climbers would find daunting.

By the time he finished in 2010, he had climbed the most challenging mountains imaginable – including Mt. Everest.

He says the constant life-or-death decisions required on these climbs is what kept him going.

“Most decisions we make on a typical day are absolutely inconsequential,” says Slakey, the Upjohn Lecturer on Physics and Public Policy at Georgetown. “Things like do we want paper or plastic. What I’ve faced over the years in climbing have been really significant moments that aren’t just a physical test – they are also mental and spiritual, and they are significant and transformative.”

A Time of Reflection

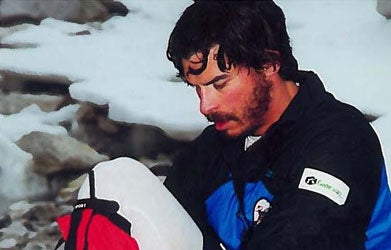

The Georgetown professor at a camp in Denali National Park, which is home to Mt. McKinley. He says he became a better person during his quest. Photo by Mike Farris.

Slakey says his transformation from a self-described “cold” and “insensitive” person to someone who cares deeply about others took place during his 12-year journey.

Getting trapped in a storm in Antarctica was a turning point.

“I had days of just doing nothing but staring at the tent wall and I had no choice but to reflect,” he says.

In the book, he writes that he was “alone with my thoughts. I began to reflect on why people might conclude I was cold and broken. I thought about whether I wanted to stay that way.”

He also wrote “I had thought it was my remove and self-absorption that gave me the focus to push past challenges and achieve my goals. …I had an epiphany of sorts. It was time I left my cave.”

Ambushed

Facing an ambush by guerillas in Indonesia also had a big effect on the professor.

Slakey escaped the attack, but others weren’t so lucky. Days later, two Americans were killed in an ambush at the same location. Eventually one of the survivors, Patsy Spier, would become his friend.

“I dodged a bullet,” Slakey said. “I had plenty of close calls before, but never one where someone else took the hit instead of me. That changed me.”

Slakey testified before the Homeland Security Committee about the incident while Patsy Spier relentlessly pressed for an investigation. He says she was successful and that the shooters were hunted down and are now in jail.

Over time, the professor’s attitude toward the world and its people changed.

“There was a time when I would look at a map and all I would see would be oceans to surf, mountains to climb,” says the professor, who founded and co-directs Georgetown’s Science in the Public Interest (SPI). “Now I look at a map and I see global challenges. I look at the map and I see people struggling to get clean water, people fighting disease, climate change.”

Married and Connected

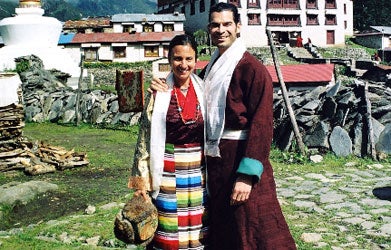

Slakey married his wife, Gina Eppolito, after meeting her on Mt. Everest.

And he learned how to connect to others. He once vowed never to have a wife, own a home or have children. He now has all three.

Slakey met his wife, Gina Eppolito, on Mt. Everest, they later returned to marry there, in 2004. Now they live in a house in Washington, D.C., with their twin 2-year-old girls, Zaida and Kinley.

“There are so many similarities in her upbringing and mine, but she came out of it so different,” he says. “She’s relentlessly positive, in a practical way.”

Introducing Laws

The professor now brings the challenges he’s witnessed into the classroom, where SPI students learn how to propose bills to Congress or ameliorate global or national problems.

Since the program’s inception in 2007, three student ideas have been signed into law by the president of the United States. One of them was federal support for campuses that build green buildings, another is a loan forgiveness program for nurses and the other stipulated the use of national laboratories to help train high school science teachers during the summer.

His student groups have also won grants to travel to Mali and to India to work on their projects.

“They’re steering our journey to a better place,” he says of their work.

Sense of Justice

Francis Slakey’s book will be published in May.

“They come into the classroom with no experience in politics or policy and they come out having laws introduced or contributing to the solution of a global challenge” Slakey says of his students.

Patsy Spier inspired him, he adds.

“I think the lesson that I learned from Patsy Spier is so powerful,” Slakey says. “It can seem daunting, the forces out there that can oppose us in one way or another. But with enough will and a sense of justice, the right thing can happen.”

Original Family

He didn’t always have this kind of connection with students, or with anyone for that matter.

In addition to the history of those who climbed the mountains he summited, Slakey also writes in the book about his personal history.

When Slakey was 11, his Ecuadorian mother, Zaida Sojos-Vela, died of brain cancer.

Not long after her death, a close friend died and Slakey shut down emotionally and remained that way for decades.

He says his father, Georgetown emeritus English professor Roger Slakey, did a remarkable job managing his three sons, but the mother’s death had a profound effect on the family.

Remote Control

“Cold? Insensitive? I remember thinking at the time: What’s wrong with that?” he writes in the book. “Insensitivity can come in handy, depending on how you live your life.”

His remoteness even extended to the students he taught. He says he would turn his back on them during class and draw equations on the chalkboard for 50 minutes and passed out a test every eight weeks.

“Mechanical, sterile, and with assembly line efficiency, all students had to do was listen and learn,” he writes.

Changing Perspectives

Climbing toward Mt. Everest. The experiences Slakey experienced during his journey inform his classroom teaching today. Photo by Mike Farris.

Now he is constantly engaged with his students.

Derick Stace-Naughton (C’11) uses a familiar Slakey word when he calls the professor’s classes “transformative.”

As an SPI student, the Georgetown alumnus got a bill introduced that would require the federal government to create a series of measures, including grants to provide screenings, for a genetic disorder.

He and his mother and sister all suffer from the disorder, which prevents their blood from clotting properly.

“They change the way you think about science,” Stace-Naughton says of Slakey’s courses, “and whether you like it or not, they put you out past the gates of the university.

Been There, Done That

At 48, Slakey no longer climbs mountains or surfs oceans.

“I’ve done all the mountains I wanted to do,” he says. “The other reason I’m done with it is that these are really elegant sports. When you see somebody who’s good at it, it’s beautiful to watch. I’m not either anymore.”

His final reason for leaving extreme sports activities behind is the reason he started in the first place.

“I’ve been transformed enough,” he says. “I don’t need it like I used to.”