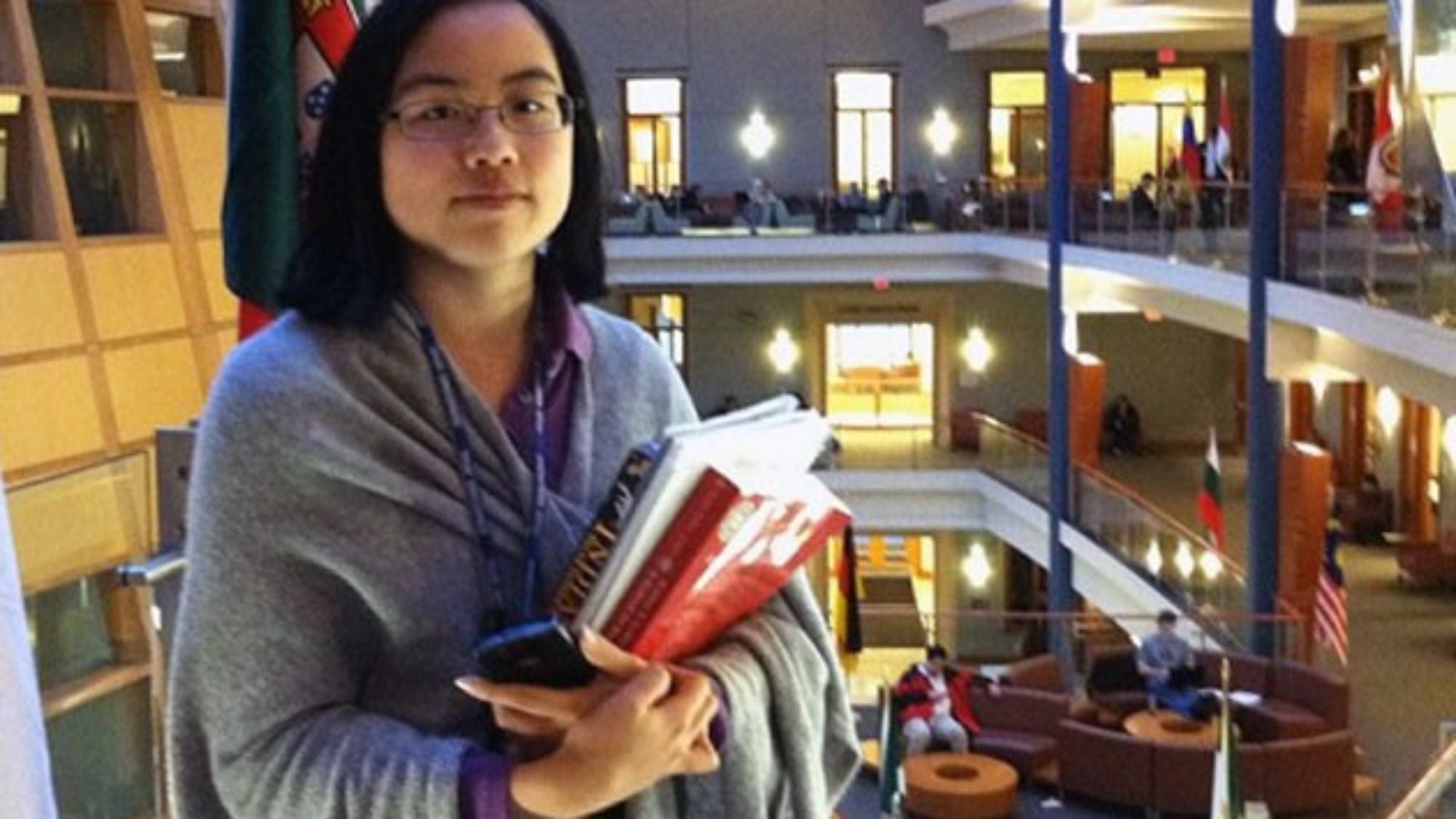

Title: Autistic Student Advocates for Herself, Other Autistics

In a recent “Autistic Hoya” blog post written by Lydia Brown (C’15), the first-year student lists “15 Things You Should Never Say to an Autistic.”

These include “Is that like being retarded?” and “Does that mean you’re really good at math/computers/numbers?”

Brown, an Arabic major who hopes to one day get a Ph.D. in Islamic studies, is an advocate for herself and other autistics. One of her priorities is getting rid of the stereotypes that surround autism.

“People ask, when they hear about my advocacy work, ‘So you have a family member who is autistic?’ ” Brown says. “The implication is that an autistic person couldn’t possibly be doing this. One of the most hurtful things people can say, which apparently is meant to be a compliment, is, ‘You look so normal,’ or ‘you don’t look autistic.’ ”

Resources, Petitions

Brown’s advocacy work is wide-ranging. She convinced members of the legislature in her native Massachusetts to propose a bill requiring that law enforcement officers learn about autism while she was still in high school.

She has created an online resource and advocacy website called the Autism Education Project, and established an online petition to protest a Kentucky school aide’s placement of an autistic boy in a bag to “control his autistic behavior.” To date, the petition has more than 190,000 signatures.

The first-year student also serves as an intern with the Washington, D.C.-based Autistic Self-Advocacy Network, has spoken at one autism conference and will speak at two or three others this year.

Brown is also a member of the National Youth Leadership Network’s Outreach and Awareness Committee. And she will serve as a member of a consumer advisory council for the Georgetown University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities at Georgetown’s Center for Child and Human Development for the next five years.

Changing Views

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, autism spectrum disorder is a “range of complex neurodevelopment disorders characterized by social impairments, communication difficulties, and restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior,” with Asperger syndrome considered a “milder” condition on the autism spectrum.

That distinction is likely to change with the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which psychiatrists have long used for diagnosing patients. In the new edition, only autism will appear.

Brown, an Arabic major, is working on her fifth and sixth crime fiction novels and has at least some understanding of eight foreign languages.

She believes autism shouldn’t be in the DSM at all.

“A lot of the people in the community don’t like the word disorder,” Brown says. “I don’t really like the word disability either, but it’s accurate in the context of our society. We’re differently ordered but not disordered.”

Neurodiversity Movement

This view is part of the neurodiversity movement, which is also against the idea of finding a “cure.”

“Because we see autism and other neurodevelopmental or neurological differences, conditions or disabilities as a natural variation of human diversity in terms of neurological diversity,” Brown says, “that means there’s nothing defective, wrong or diseased or broken. Therefore there’s no reason for a fix or for a cure.”

Taking medication for co-occurring conditions such as ADHD, depression and anxiety, should only happen if the autistic person believes it will improve his or her quality of life, she says.

Another controversy has to do with how she wishes to describe her disability. She prefers saying “autistic person” versus “person with autism,” a topic of debate among the autistic community.

Speaking for All Autistics

Brown siding with the neurodiversity movement irks some parents of autistic children, particularly non-autistic parents.

“You can imagine it might be very easy for a parent of a non-speaking child who slams his head into walls to look at someone like me and say, ‘You don’t understand what it’s like to be disabled.’ But the neurodiversity movement is not just for people like me.”

She is often asked how a highly verbal college student can speak for severely disabled autistics.

“While every autistic person has different needs and abilities, that doesn’t mean that I can’t speak to the commonalities I have with autistic people who do not present the same way as I do,” says Brown, whose parents adopted her from China. “Autistic people understand other autistic people’s experiences far better than any non-autistic person simply by the very nature of also being autistic.”

Personal Difficulties

Lydia Brown sits on a table in classroom”We’re differently ordered but not disordered,” Brown says.

Though obviously not severely disabled, Brown has her share of issues to deal with.

She says she has symptoms of spatial agnosia, which somewhat impairs her ability to localize objects or appreciate distance, motion and spatial relationships, as well as dyspraxia, which affects movement and coordination.

These problems result in numerous bumps and bruises for Brown, who stands a little over 5 feet tall.

She also says she has traits of sensory processing disorder, which means she can get easily overwhelmed by visual, auditory, tactile or other sensory input.

Brown speaks Spanish, “passable but bad” Portuguese, understands some French and some Italian, reads a little German, Swedish and Haitian Creole and is working on her Arabic.

“If taught in the right way, and I only learn visually, I can learn languages very quickly and accurately,” she explain. “I need visual support. You can’t lecture at me or speak at me and you can’t play CDs at me. I need visual support and a visual aid for everything.”

Massachusetts Legislation

Massachusetts Legislation

Sarcasm is incomprehensible to her.

“If a police officer were being sarcastic, I would not know,” she says. “ And if the officer did not realize that I wasn’t picking up on the sarcasm, the officer would just think I was being defiant.”

She is still hoping the Massachusetts legislation will get passed, though it recently died in committee. She plans to re-file the bill in the 2013-2014 legislative session.

“This training, if done right, will teach officers appropriate de-escalation techniques for developmentally disabled people,” Brown says.

She says officers who don’t get such training have accidentally arrested, inappropriately restrained or used Tasers on autistic people, exacerbating meltdowns and prompting lawsuits that end up hurting departments financially.

Sense of Justice

Lydia Brown in a suitBrown says she wants to get rid of the stereotypes that surround autism.

Being autistic has its advantages, she says.

“Because I am autistic I like to be very detailed and meticulous and accurate so I’ve actually read a bunch of statutes and I’ve read a bunch of federal policies … in order to make a vague reference to something that would be accurate,” she explains.

Brown says she is writing her fifth and sixth crime fiction novels simultaneously and plans to take Farsi in the fall because of her interest in Sufi poetry.

Recent research has indicated that despite the stereotypes, autistics are sometimes more empathetic than non-autistics.

“Being autistic gives me a different outlook on the world than if I weren’t autistic,” Brown says. “I think it gives me a stronger sense of justice.”