August 15, 2021, was the worst, most difficult day of my life.

There were no flights out of Afghanistan. I was on the tarmac in the dead of night with nowhere to go. The Taliban was all around the airport, and my country had just fallen under their control. I hadn’t eaten or slept in 36 hours. I watched desperate attempts to leave, including a mother in distress after being separated from her two-year-old daughter.

But I never panicked. In those 36 hours at the airport, I knew there were people trying to help. I was embedded in a broader community of humans, who, on the worst day of my life, were there to try to take care of me and help me.

I’ve often found that acts of unexpected kindness have changed the trajectory of my life.

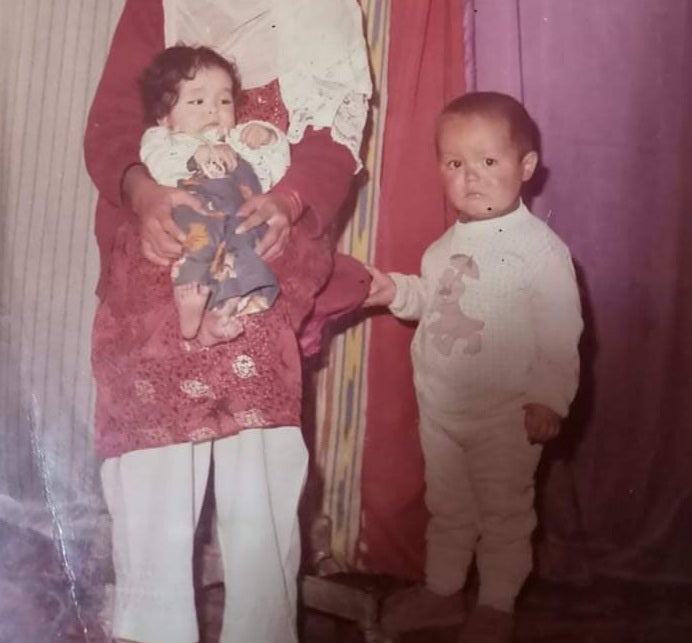

1993: A Refugee in Pakistan

I was about six years old when my family left Afghanistan to become refugees in Pakistan. It was during the country’s civil war. Our journey to the border was similar to the protagonist’s journey in “The Kite Runner.”

One night, my mother and I were in a wobbly taxi driving through checkpoints with men with guns. Night fell, and we stopped in a rural village. A family took us in and fed us rabbit soup. They didn’t have much, and they were from the opposite, dominant ethnic group. There had been violence between our two groups. But we came to their village, and they took care of us.

My mother and I made it to Pakistan safely and reunited with my father.

*

As a refugee, you have to work harder to distinguish yourself. My grandfather persuaded the teacher at our community’s English learning center to teach me English for free. That made all the difference – English is what really helped me get out of that dusty town.

In high school, an American family working in his community encouraged Jamal to study in the U.S. They bought him an SAT preparation book and signed him up for a test in Islamabad. A few months later, he received a scholarship from Berea College in Kentucky.

I thought maybe I can do something more. All the possibilities of life opened up.

That family’s decision to take us in that one night had a lot of positive effects. My grandfather making sure I learned English, an admissions committee taking a chance on me – kindness changed the entire direction of my life.

2012: A Return to Afghanistan

After graduating from Berea College in 2011, Jamal began working for a nonprofit in Washington, DC, where he proposed and ran a scholarship program to fund college opportunities in the U.S. for students in Afghanistan.

I wanted to give other kids the same kind of opportunity that I had. I reached out to colleges to secure a full ride for scholars, primarily young women. We ended up helping five kids.

An opportunity to study in the U.S. had made all the difference in my life, and I thought that would change other people’s lives as well.

*

A year later, I went back to Afghanistan. A lot of people told me that was the wrong decision. Everybody was leaving. Why are you coming back?

I realized that Afghanistan was a place where you could work and make a difference. The U.S. was so well-built that somebody like me could only be a brick in that wall. But in Afghanistan, there was this possibility of helping to build that wall. I wanted to be part of that rebuilding process.

Rebuilding With a New Tool

Jamal worked at Human Rights Watch for four years. While at the organization, Jamal also co-founded Impassion Afghanistan, the country’s first digital media agency that empowered citizen journalists to monitor voting conditions across the country and encourage Afghans to vote. During this time, he realized that fighting for human rights involved more than advocacy.

While working for Human Rights Watch, it became clear that activism was about building a case slowly over time. With policy, given the right window, you can slam-dunk. I thought it was easier to make a difference in policy. The laws and policy you make have a bearing on the rights of people. A sort of lightbulb popped up.

I was offered a Fulbright scholarship, and decided to study at the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown. In my admission essay, I wrote that public policy is an important instrument to further human rights.

I wrote that because, when I was very young, we lost my younger sister, Shogofa, to something that was preventable. She was three years old.

After her, we lost my brother, Qiyam, to pneumonia, another preventable cause. He passed away around the age of six months.

Children in the developing world die of preventable causes, like pneumonia. And that is not a failure of medicine. That is not a failure of nutrition. It’s a failure of public health. It’s a failure of public policy. I wanted to get the skills at McCourt that would help me make a difference in human rights and the right to life through public policy.

I decided to study at Georgetown primarily because of the DC location. If you’re studying public policy, there’s no other city more conducive to that study. And the city has the most powerful legislature in the world whose decisions can make or break nations and make a difference in the lives of young boys in Afghanistan, dying of pneumonia.

2017: Applying Jesuit Ethics to the Taliban

At McCourt, Jamal served as the editor-in-chief of the Georgetown Public Policy Review, the school’s peer-reviewed academic publication. He took classes at the McDonough School of Business, the Walsh School of Foreign Service and Georgetown Law to tailor his curriculum to his career needs. And he encountered the school’s Jesuit values and approach to education for the first time.

One of the things that really struck me about McCourt was its class on ethics in public policy. Because of Georgetown’s roots in Jesuit teaching, the curriculum helped us think about ethics when we were making policy — what sort of policy choices would advantage or disadvantage one group over the other. Cold, hard data alone does not always tell you what to do for the greater good, which is why you need ethical and equitable frameworks to work with. And that’s what the ethics class was all about.

*

After graduation, I joined the National Security Council in Afghanistan as director for peace and reconciliation initiatives. My job was to offer support at a policy level to the team that negotiated with the Taliban. I also worked on policy procedures that would reduce civilian casualties in war time. In a later position, I helped make sure that Afghanistan’s national security diplomacy abroad reflected our national security priorities.