Anne Marie Becraft kept her school for black girls in Georgetown open until 1831, when she moved to Baltimore to join the Oblate Sisters of Providence (OSP), the first African American female religious order in the country, and soon took the name Sister Mary Aloysius.

“I’m thrilled that we decided to rename one of our buildings after Anne Marie Becraft,” says Marcia Chatelain, , associate professor of history and African American studies and a member of the Georgetown University Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation. “She was a devout Catholic and deeply committed to educating young girls of color in the nation’s capital. Though she experienced both anti-Catholic and anti-black intimidation, she nevertheless responded to her calling to teach and to serve God.”

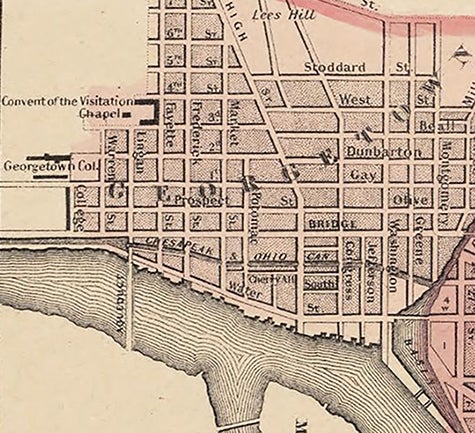

Becraft began her teaching career at age 15 in 1820, founding a school on Dumbarton Street in Washington, D.C. Her intelligence and work ethic attracted the notice of Rev. John Van Lommel, S.J., from Holy Trinity Church in Georgetown.

‘Elevation of Character’

Van Lommel was so impressed with Becraft’s work and “elevation of character,” that in 1827 he “took it in hand to give her a higher style of school in which to work for her sex and race, to the education of which she had now fully consecrated herself,” according to The History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880, published in 1885 by African American historian George Washington Williams.

The new school on Fayette Street, which included 30 to 35 students, was across from the Monastery of the Visitation, established in 1799 by Rev. Leonard Neale, S.J., president of Georgetown from 1798 to 1806.

Williams called Becraft “the most remarkable Colored young woman of her time in the District and perhaps of any time.”

In 1831, she left her school in the hands of a promising student and moved to Baltimore to join the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the first African American female religious order in the country. She took the name Sister Mary Aloysius.

Uneasy Times

Becraft’s success came amidst challenging times for free people of color.

She did not have the right to own property or the right to vote. “She lived in a society in which slavery and racism were firmly entrenched, yet even in such a society she was able to stimulate in her students a desire for educational attainment,” according to the scholarly encyclopedia Black Women in America.

According to a 1969 Maryland Historical Society article, “The Free Negro Population of Washington, D.C., 1800-1862” by Henry S. Robinson, an 1821 law in Washington required people of color to “appear in person before the mayor and to show their proof of freedom.”

“They were required to show the mayor a certificate signed by at least three respectable white citizens stating that they were of good character,” the article states. “If free people of color were unable to provide such evidence, they were liable to arrest and imprisonment as absconding slaves.”

A Brave Woman

After she passed away in 1833, Becraft’s influence in Washington and Baltimore was noted in a number of history books and reports.

“[Becraft] is remembered, wherever she was known, as a woman of the rarest sweetness and exaltation of Christian life, graceful and attractive in person and manners, gifted, well educated, and wholly devoted to doing good,” according to an 1870 special report submitted to the U.S. Congress on the “Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia.”

It was Becraft’s bravery in antebellum Washington, her devotion to education and her faith that led Georgetown’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to recommend that the building known as Remembrance Hall be permanently renamed in her honor.

The building was originally named for Rev. William McSherry, S.J., a Jesuit at Georgetown involved with the 1838 sale of more than 270 enslaved individuals owned by the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus that benefitted the university. That name was temporarily changed to Remembrance Hall in 2015.

Another building named for Rev. Thomas Mulledy, S.J., and temporarily changed to Freedom Hall the same year, will be permanently named Isaac Hawkins Hall on April 18.

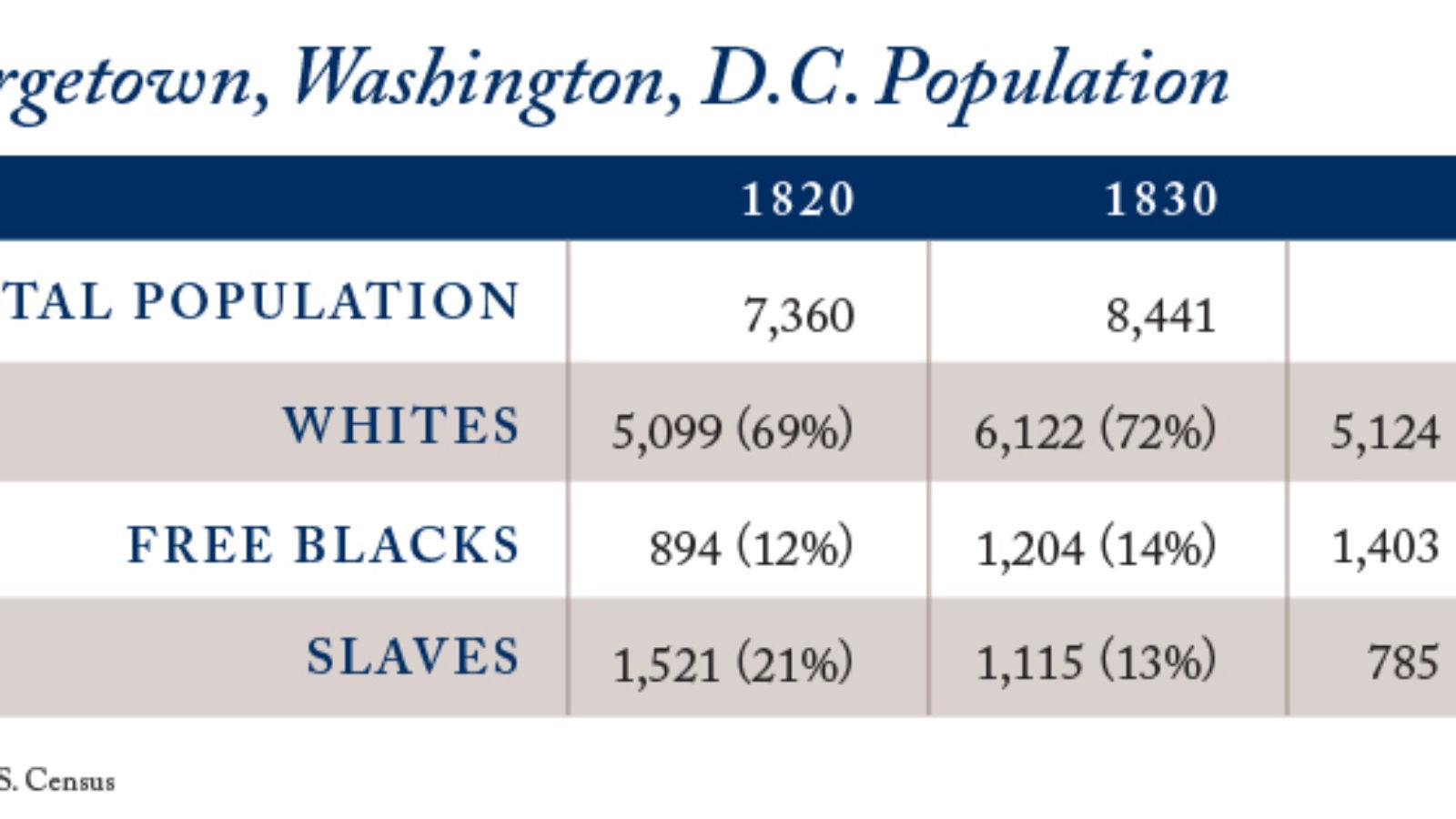

Free People of Color

There were a significant number of free black people living in the District in the early 1800s, according to Black Georgetown Remembered, published in 1991 and reprinted in 2016 by Georgetown University Press.

There were also many Catholics of color in Washington, D.C., according to a 1990 book, The History of Black Catholics in the United States, by Cyprian Davis, O.S.B.

Davis attributes this to the city’s “proximity to the Southern Maryland area … where there had always been a large black Catholic presence.” He notes that both blacks and whites worshipped at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown and that poor children of all races were taught for free by the parish.

Continued Learning

Becraft’s own education began at an early age at schools that taught both white and black children. Mary Billings, an English white woman, ran the second school Becraft attended.

The establishment closed in 1820, the same year Becraft began her own school. According to Black Women in America, the Billings school closed because “white involvement in the education of black people was discouraged.”

Maurice Jackson, a Georgetown professor of history and African American studies, says the first public schools for whites opened in the District in 1806 and that free blacks such as Moses Liverpool, George Bell and Nicholas Franklin started the first black school there in 1807.

“However, teachers were not allowed to do anything that the authorities thought might help slaves gain their freedom,” Jackson says.

He notes that in 1810, a woman in the District named Althea Turner bought her freedom and later that of her sister and five of her children. She also helped 12 other black people become free.

“That same year, Mrs. Billings began to teach black children in her home and did so for eleven years,” Jackson says. “This is the lofty heritage that Anne Marie Becraft inherited and this is the distinguished tradition that she added to.”

Devout and Religious

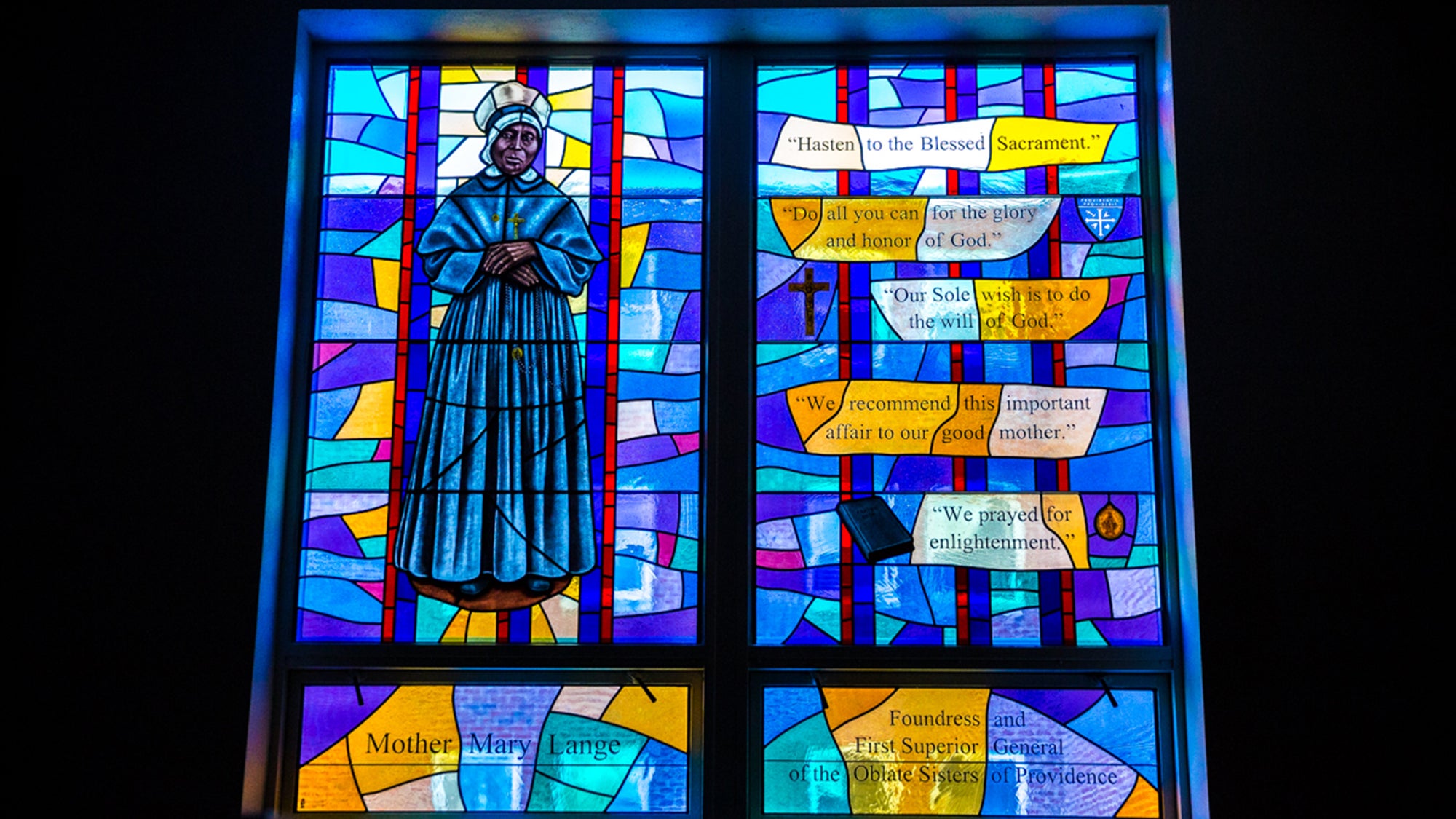

A Catholic priest and four women founded the Oblate Sisters of Providence religious order only a few years before Becraft joined it.

“Becraft’s involvement with these sisters places her life squarely within the context of the Atlantic world of the early 19th century, where people and ideas from North American colonies, European metropoles and African societies were continuing to encounter, meld and create new communities,” explains historian James Benton (G’08, G’11, G’16), Georgetown University’s Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation Fellow.

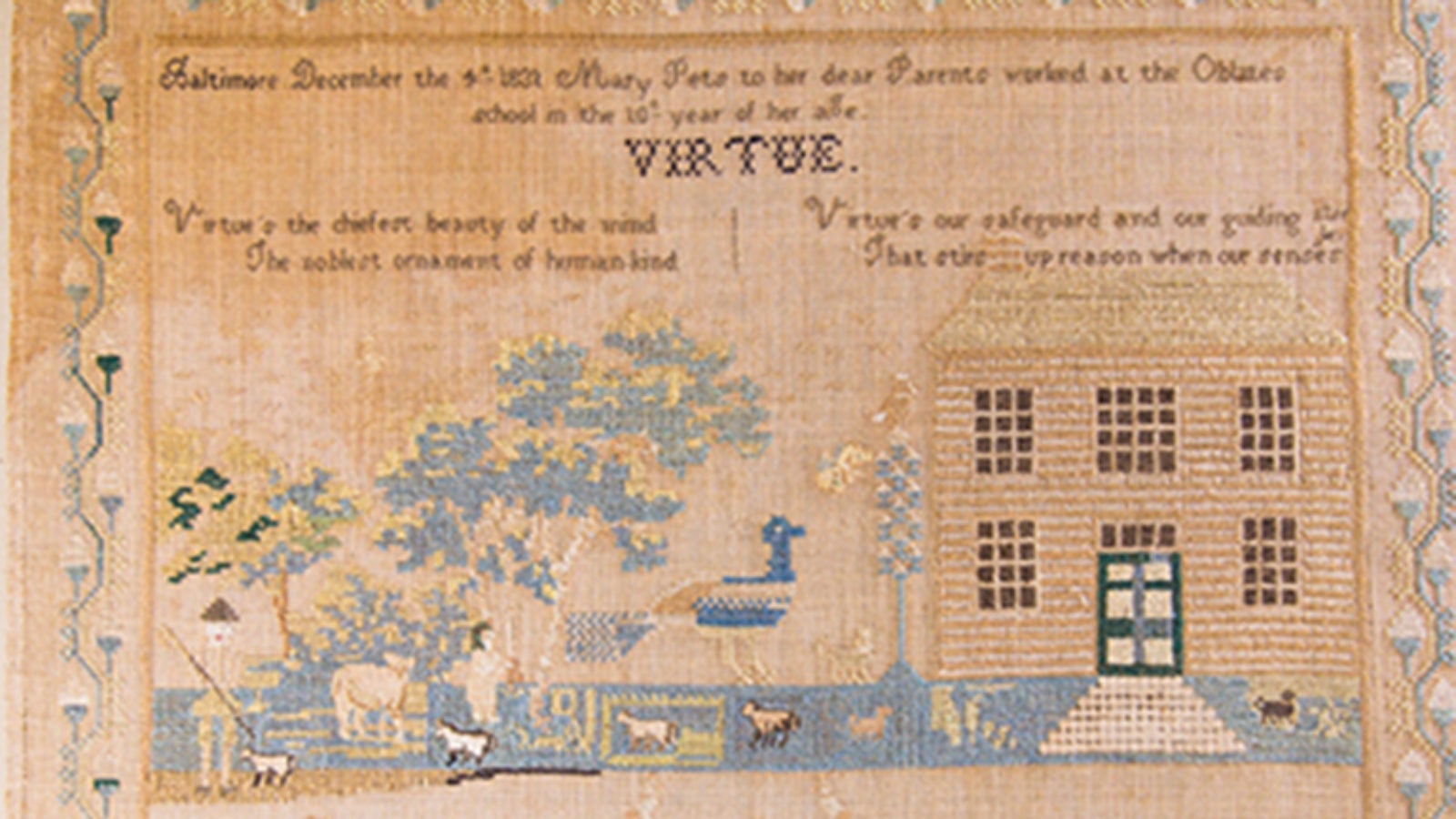

The religious order opened the Saint Frances School for Colored Girls in Baltimore in 1828.

The school’s name was changed in the mid-1800s to Saint Frances Academy, and it is now the oldest continuously operating predominantly African American high school in the United States.

While she was there Becraft taught girls of color who ranged from about age 8 to 14.

Two of her sisters, Rosetta and Susan, both boarded and attended the Oblate Sisters’ school. Susan decided to join the order but had to leave due to illness.

“In my view, Becraft came not only because she loved teaching children and thought that was so necessary, but because she was a very devout and religious woman,” says Sharon Knecht, the Oblate Sisters of Providence’s archivist. “Here she could combine the two loves of her life. And it was a perfect fit for her.”

Sisterly Habits

According to Knecht’s 2007 book, Oblate Sisters of Providence: A Pictorial History, the habits the sisters wore comprised a “full-pleated, long-sleeved black dress trimmed with a white collar. A crucifix was attached to the area over the heart.”

A black band worn on a white bonnet distinguished the professed sisters from the novices, the book explains.

When they traveled outside the convent, however, they wore black bonnets, possibly to avoid attention.

While Knecht says there is no evidence the Oblate Sisters were harassed, she adds that these women organized to serve God and their community “in a time where some people believed that people of color didn’t even have souls. So for these women to have that much strength and conviction to overcome what they had to overcome is truly amazing and heroic, in my eyes.”

A Short Life

According to the Oblate Sisters’ archival records, Becraft was with the order only two-and-a-half years before she died at the age of 28 in December 1833 from a “chest malady of which she felt the first attack when she was 15 years of age.”

“In spite of her ill health, this pious girl rendered herself very useful in teaching English, embroidery and arithmetic;” reads the Oblate Sisters’ diary for the day, “she had a very sweet disposition, joining with it the firmness necessary to make her respected by the children. Pious, humble and obedient, she took with her the regrets of all the Sisters.”

Becraft Family

Becraft was the daughter of William Becraft, who served as chief steward for many years at the Union Hotel and Tavern in the vicinity of what is now M and 30th Streets N.W., and Sarah Daniels Becraft.

William Becraft’s mother was employed in the household of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence and a cousin to Georgetown’s founder, Archbishop John Carroll.

Both parents, along with two of her sisters, are buried in the Holy Rood Cemetery on Wisconsin Avenue N.W.