Title: Antarctica Expedition Could Help Solve Mars’ Question of Life

Georgetown professor Sarah Stewart Johnson is leading a National Science Foundation-funded expedition to Antarctica later this month that may one day help solve the question of whether there was ever life on Mars.

A Georgetown professor is leading a National Science Foundation-funded expedition to Antarctica later this month that may one day help solve the question of whether there was ever life on Mars.

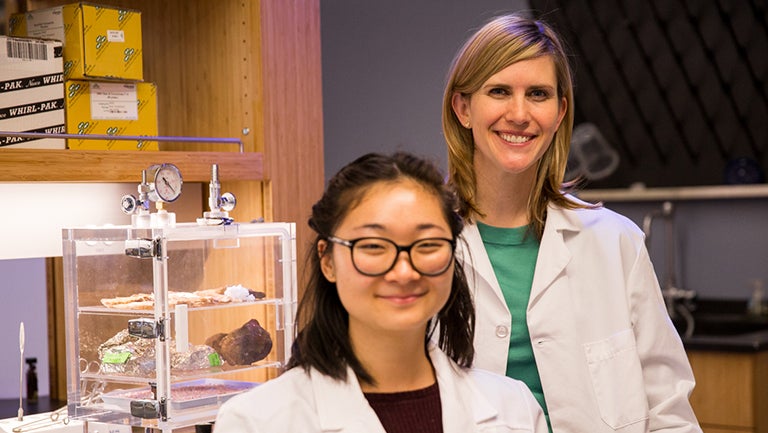

Sarah Stewart Johnson, assistant professor in the biology department and the Science, Technology and International Affairs program, is teaming up with undergraduate Angela Bai (C’17), post-doctoral fellow Elena Zaikova and David Goerlitz of the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center to conduct the first-ever DNA sequencing on the continent.

The work, which will begin after Thanksgiving and last for about a month, takes place in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, just across the sound from the U.S. Antarctic Program’s main base at McMurdo Station. The researchers plan to blog about their experience.

Cell Survival

“We’re testing a series of questions about the nature of long-term cell survival under cold and hyper-arid conditions,” says Johnson, also a visiting scientist at the NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and a member of NASA’s Curiosity Rover Science Team.

The McMurdo Dry Valleys are home to some of the most physically and chemically extreme environmental conditions in the world. The Georgetown team will study whether microbes within ice-covered lakes can survive desiccation as the lakes retreat, and if so, how.

“Mars and Earth used to be much more similar,” notes Johnson, who teaches courses in geobiology as well as planetary science. “Like the Earth, Mars once had lakes, but not anymore. Because it’s smaller and further from the sun than Earth, it cooled down more rapidly.”

“It also lost its protective magnetic field and most of its atmosphere, and now is bitterly cold and extremely arid,” she adds. “If life did evolve there, what’s become of it?”

Johnson says that Antarctica is the “coldest, driest place on Earth.”

“We believe the paleolakes there provide an unrivaled opportunity to investigate fundamental questions about the persistence of life,” she explains.

A Close Second

The project is creating an unusual research experience for an undergraduate.

“I love genetics and I love space, so I was a little sad to have missed out on the first DNA sequencing in space, but Antarctica is definitely a close second,” says Bai, a biology major from Pasadena, California, who works in Johnson’s

“I love genetics and I love space, so I was a little sad to have missed out on the first DNA sequencing in space, but Antarctica is definitely a close second,” says Bai, a biology major from Pasadena, California, who works in Johnson’s lab.

She’s looking forward to being part of the first sequencing on the continent.

“We’re all hoping for robust samples that will give us a bunch of DNA to analyze, and that the ultimate results will be fascinating,” Bai says.

Once in Antarctica, the team will go out into the field with a state-of-the-art instrument called the Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencer, which is about half the size of a cell phone.

The instrument will help the team figure out whether the Antarctic paleolakes harbor “microbial seed banks,” caches of viable microbes that adapted to past environments.

“This kind of data is revolutionizing our ability to observe and understand our planet’s most inaccessible biospheres, and we may one day be able to use the technology to look for life beyond Earth,” the professor says.

Classroom Applications

Johnson will bring back the Antarctic research to Georgetown, where she is piloting new undergraduate geoscience courses that incorporate case studies.

“This project will allow us to use real data sets to understand geoscience concepts,” she explains, “such as the complexities of adaptation to climate change in high latitudes.”

Goerlitz is director of operations for the Genomics and Epigenomics Shared Resource at the Lombardi Center, where he runs a lab focused on providing state of the art technologies and expertise for genomics research to Georgetown scientists.

“The work in Antarctica has important implications for understanding how life, adapted to extreme environments, can persist at the margins of survival, “ Goerlitz says, “and will ultimately inform the development of life detection strategies in the planetary sciences, particularly in the search for life on Mars.”

Exploring Other Worlds

Johnson, a Rhodes scholar with a Ph.D. in planetary science from MIT, says she first became interested in her field as a child in Kentucky, where her father was an amateur geologist and astronomer.

In her first year at Washington University in St. Louis, she worked with a professor on the prototype for the Mars Spirit and Opportunity rovers. She was part of a team that went out into the Mojave Desert to take measurements.

“I fell completely in love with the idea of exploring other worlds,” she says

“Planetary science is a field that’s really wide open. There’s so much left to discover. In some ways it’s like being an earth scientist 100 years ago.”

Coincidentally, Georgetown Provost Robert Groves will be in Antarctica at the same time that Johnson’s group is conducting research.

As a member of the National Science Board, which governs NSF, he will be part of a team inspecting two of the three Antarctica science operations – McMurdo and the South Pole.