Janet Mann loves dolphins.

Ever since she traveled to Australia to study dolphins in graduate school, she has dedicated her life to studying these marine mammals. Her research focuses on the social networks, calf development and culture of dolphins.

Dolphins fascinate the Distinguished University Professor, so much so that her husband convinced her that they should buy a cottage three hours away from her Washington, DC, office and down the Potomac River to get her away from work from time to time.

To say the least, everything did not go according to her husband’s plan.

“The day we closed on the house, I looked in the backyard, and there were dolphins swimming by,” said Mann, who has appointments in the Departments of Biology and Psychology in the College of Arts & Sciences and does work with the Earth Commons Institute. “My husband looked at me and was kind of excited there were dolphins, but he was also like, ‘Uh oh.’”

When Mann is not at Georgetown, you’ll likely find her downriver on the deck of a boat named Ahoya in the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac studying dolphins, many of which Mann and her team have named over the years. Grover Cleveland, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Bill Clinton — the dolphins — are regulars in Mann’s neck of the waters in the Potomac.

During the summers, Mann spends a couple of months in Shark Bay, Australia, where a large dolphin population lives. At about thirteen thousand miles away from DC, Mann says you’d be hard-pressed to find two research sites farther away from each other on the planet.

But Mann wouldn’t have it any other way.

Recently, Mann and several Georgetown co-authors published a study funded by an Earth Commons “ECo Impact Award,” which found that fostering connections between people and individual animals could promote more environmentally friendly attitudes and conservation efforts.

Discover what makes dolphins fascinating creatures, what Mann loves about her work, and why she and her team give fun names to the dolphins they study.

Behind the CV: Janet Mann on Dolphins and the Importance of Animal Storytelling

Loving nature on Long Island: My mother was a birder, but I wasn’t terribly interested in birds. We always had lots of National Geographic magazines around, and I saw Jane Goodall on television when I was 14 [and saw you can study wildlife] for a living. I grew up on Long Island, and unlike most of the Long Islanders I grew up with, I hated shopping. Seeing Jane Goodall, a woman out in the middle of the forest studying chimpanzees, seemed like a much better alternative to spending time at the mall.

Growing up by the water: I spent my summers working in Montauk on the end of Long Island. It wasn’t the fancy-schmancy place like it is now, but I used to camp and work out there. I worked on the docks with fishermen, so I was comfortable around boats and the watermen. I was interested in what they were doing, and they had a whole culture unto themselves.

How I came to study dolphins: Entirely by accident. I was planning to become a primatologist studying both human and non-human primates. When I was in graduate school at the University of Michigan, my advisor, who was a primatologist, got interested in starting this dolphin project in Australia, and she asked me to come and help. At the time, there were already many great primatologists doing fieldwork, and there was very little known about dolphins, so I thought I had a lot more to contribute by studying dolphins. I actually started studying dolphins before I really knew anything about them and hadn’t planned it. It was just that free trip to Australia to study dolphins, and then I got hooked.

Why dolphins fascinate me: Dolphins have very large brains and have had large brains for millions of years longer than humans have. We’re enamored with our own brains, but here are [a group of] species in the water that aren’t building anything and yet have evolved high intelligence.

What dolphins share with humans: Dolphins have what we call individually specific long-term bonds, just like humans have. Humans have ‘besties’ and individuals we have known for decades. Dolphins do too. They have lifetime bonds, something which is rare in nature. They maintain these relationships, but they’re not together all the time. Dolphins have that kind of dynamic social life that’s rich and lasting.

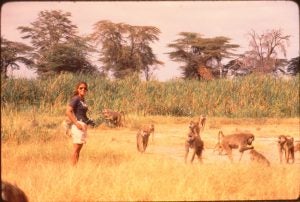

I love research because: There are all these ‘why’ questions about wildlife. Why have dolphins evolved big brains? Why are baboons in troops? Why do they have these social bonds? Research is the best way to find out and not just satisfy my curiosity, but I also have an obligation to the public to convey the lives of wild animals and what our findings are. It’s a real privilege to be around wildlife, where they let you in, they let you be there and witness their lives. Very few people in the world get to see anything like this. It’s an honor to be kind of accepted enough by another species that they won’t run from you or swim away.

The importance of telling animals’ stories: If you tell people about the lives of animals as they are, it takes them a bit outside of themselves because it’s not anthropomorphizing as a lot of other animal stories are. My hope is that people can relate to and have empathy for the animals outside of themselves by trying to understand what their lives are like. To protect animals, you need to understand what their lives are like. This includes their social and reproductive behavior, ecological and spatial behavior (predators, resources), and risks they face from human activity.

Finding dolphins in the Potomac: I did know that dolphins were there in the 1800s. But I thought that they [left] because of pollution, human activity, the decline of fish populations and what have you. [After we found dolphins,] for a while, I turned our house into a field station, and we started a project down here. So much for getting me away from my work!

How we find dolphins: If we’re looking for specific individuals, we go to their favorite hangouts. Each dolphin has a distinctive dorsal fin. We don’t tag them. We photograph them, and we match them up with the catalog, so they’re all identified by their dorsal fins. In the Potomac River and Chesapeake, finding dolphins is a bit more difficult as they move around in large groups looking for fish. We can spend hours searching, but it is rewarding as we typically find dozens of dolphins at once, with group sizes sometimes exceeding 200. We have identified over 2,000 dolphins that use the Potomac River.

Why we name dolphins after historical figures: Dolphins have names for themselves. They have whistles that function as a name, but we don’t know their real names (i.e. signature whistles). It helps us remember them by giving them names rather than numbers and letters. It’s really just for our own entertainment as well. I’ve learned a lot more history because I would read up about each of these individuals. It’s fun because we see them swimming in bipartisan groups. But we’ve got all these Democrats and Republicans and individuals who hate each other getting along just fine out in the water.

The most rewarding part of my work: It’s the process of discovery. Every year, dolphins do something that surprises me. But the students are the most rewarding. Being able to introduce them to the life I love in vivid ways, that kind of experience is life-changing for them.