Title: Black Student Alliance Celebrates 50-Year Legacy of Community and Support

Georgetown’s Black Student Alliance (BSA) celebrates its 50 years of addressing and amplifying the African American experience on campus.

Georgetown’s Black Student Alliance (BSA) has addressed and amplified since 1968 the African American experience on campus, and that legacy continues as the organization marks its 50th anniversary.

“I truly couldn’t imagine my Georgetown experience without BSA,” says Lauren Smith (C’18), a recent graduate who served as BSA president 2017-2018.

Smith, a Conyers, Georgia native who majored in government and sociology, says her college career marked a formidable time of identity affirmation, and BSA provided her a safe space for authenticity and community.

“I hope that underclassmen can benefit from [BSA] as a starting point to finding their footing here,” she says. “No matter what other spaces make them feel uncomfortable, they can always know that within BSA …, they have the freedom and power to be themselves.”

Smith will work in youth development this fall in Swaziland through the Peace Corps.

The Alliance over the years has promoted an increase in programming for black students, faculty and staff through panel discussions, film viewings and professional development events for its members.

Tumult and Change in 1968

Only half a century ago, the country was struggling through social and political changes with the assassinations of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. The nation was fighting a war in Vietnam, and two black Olympians stood on their podiums with raised fists during the “Star-Spangled Banner” in protest of racial discrimination in the United States.

Led by Bernard White (C’69)the first African American to play for Georgetown’s basketball team, Georgetown’s small, yet influential, African American student community saw a time fraught with tumult and change as an opportunity to create the BSA.

“When I arrived, I was one of 30 African Americans in an undergraduate community of 6,000 students,” reveals Conan Louis (I’73), who served as the organization’s president 1971-1972. “Coming from a high school in New York, where I was one of two African Americans, the atmosphere at Georgetown wasn’t as much of a cultural shock to me as it was to my peers. But, with only 30 black students on campus at Georgetown, I don’t think people gave us much thought, except that we were very active politically.”

A Commitment Takes Shape

Students launched BSA as Georgetown’s commitment to racial justice began to take shape.

The university created the Community Scholars Program that same year in direct response to the issue of limited access to higher education in Washington, D.C.’s African American community.

By providing academic support to students in the weeks leading up to their first year of study at Georgetown, Community Scholars prepared students for the rigorous work they would face in class.

Support from the Alliance ran deep, as several students belonged to both, Community Scholars and BSA.

According to The Hoya, in 1971, the BSA raised more than $2,700 for the Community Scholars Program, which worked to garner more financial support from external sources.

Black Student Retention

One of the seminal moments of BSA was its work toward increasing black student retention and establishing a stable and safe space for students of color.

With no prior appointment made, the founding members of the organization waited outside of the office of former Georgetown President Robert J. Henle, S.J. with their, as Louis calls them, “list of demands.”

“Of the 23 black students in my class, only eight graduated due to financial and acculturation issues. Doing something about the academic retention of African-American students was at the top of our list, as well as recruiting professors and administrators,” says Louis.

The Black House

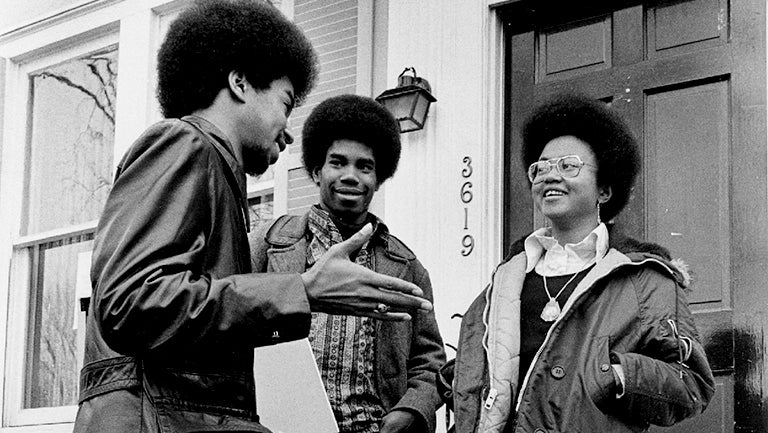

Out of this impromptu meeting with the president, organization members were able to secure a permanent meeting space and haven for black student scholarship and fellowship – The Black House.

Originally located at 3619 O St. NW, this site became a hub for studying, social gatherings, and even a pit stop for African American commuter students in between classes.

“These spaces were virtually central to the everyday survival of all the black students on campus,” shares Louis.

On- and Off-Campus Activism

Also, a search committee – on which Louis served – was established to find the director of a center that would oversee the well-being of students of color. Today, that entity is known as the Center for Multicultural Equity and Access.

BSA students not only voiced concerns about the conditions of African Americans on campus, but in the surrounding Washington, D.C. area. Early members of the Alliance organized events geared toward politics and social awareness.

That activism continues.

Encouraged by Jesuit Values

Smith says the changing landscape of Washington, D.C. makes community even more important today.

“In a city where gentrification forces out populations of color, both the Black House and BSA largely stand for the purposes of saying, ‘Yes, we’re here, and yes, we matter.’ ”

As Louis recalls his activism on campus, he says the university never tried to dismiss their grievances.

“What’s really important and what fueled my ongoing involvement as an alumnus, was that strident view of insisting on equity was something that was actually encouraged by the Jesuits,” Louis says. “They never tried to stifle my point of view, but they did enlist me to take on more leadership roles. They taught me to speak truth to power.”