Title: Chemistry Professor’s Research Looks at Reducing Foodborne Illness

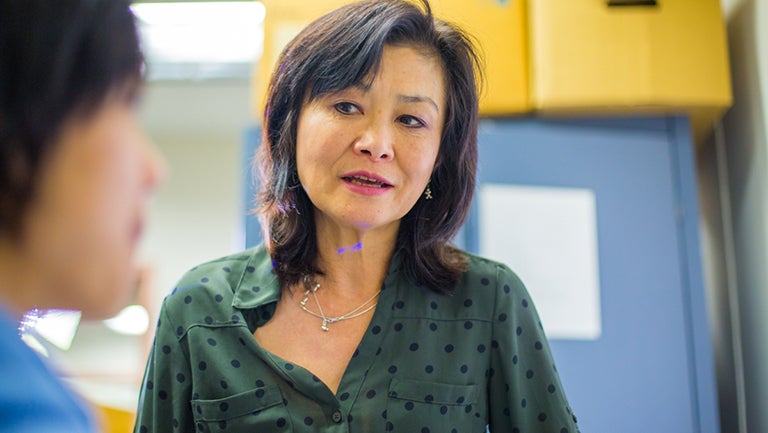

Using a recently received $ 1 million NIH grant, Georgetown chemistry professor Toshiko Ichiye is conducting research that could contribute to the fight against foodborne illness.

A Georgetown chemistry professor is conducting research that could contribute to the fight against foodborne illness using a recently received $1million NIH grant.

Focusing on enzyme functionality, Toshiko Ichiye is researching how much pressure is necessary to destroy the dangerous microbes that cause such illnesses and how to make sure the microorganisms don’t revive themselves.

Pascalization, named for the 17th-century French scientist Blaise Pascal, is the process of applying large amounts of pressure to preserve food while killing such microbes.

Killing, Not Softly

“This is a well-established process, but there is a big question about how much pressure you actually need to use to kill the microbes,” says Ichiye, the William G. McGowan Professor of Chemistry. “And not just put them into some state where when you go back to normal atmospheric pressure the microbes can survive.”

She says Pascalization has been widely used in Japan but is getting increasingly more attention in the United States.

“The reason for the interest in this is the process of Pascalization is that unlike other methods of preservation, with this method food retains its color, texture and nutritional value,” the professor notes. “When you use pasteurization you lose lots of color, taste and nutrition.”

Tricky Microbes

The microbes are tricky, though.

She says some of them produce molecules that may actually protect against pressure and that putting pressure on them activates this protective quality.

“Sugars seem to have this protective quality,” she explains. “So that could be problematic when you’re thinking about foods. You’d want to make sure that whatever you’re preserving through pressure doesn’t have a lot of sugar.”

She and her research team study enzymes from pathogenic microbes using computer modeling to vary the amounts of pressure as well as temperature.

Life in Extremes

Ichiye notes that there are many places on earth such as deserts or ocean depths where microbes and sometimes even larger organisms live, even though it seems like nothing there could possibly survive.

There are even arthropods crawling around in the Mariana Trench, the deepest part of the world’s oceans.

She also studies enzymes from microbes that live under extreme conditions.

“It’s important to understand what mechanisms these microbes are using to protect against extreme conditionsso that measures can be taken to prevent pathogenic microbes from developing the same mechanisms,” Ichiye explains. “This type of research could also have implications in the search for life in other parts of the universe.”

In related research, Georgetown biology professor Sarah Stewart Johnson, also an assistant professor in the Science, Technology and International Affairs program, led a research team to Antarctica last year to look at long-term cell survival that may one day help solve the question of whether there was ever life on Mars.

Not Blowing Up

Like Johnson’s work, Ichiye’s research could also help answer questions about extraterrestrial life. The DNA sequencing Johnson and her team makes sense to do out in the field, but testing microbes under pressure is a different animal.

“In the lab putting things under pressure is a lot harder,” Ichiye notes, and laughs. “If we put our molecule under pressure in the computer, it doesn’t blow up.”