Title: DC Immigration Advocate Named 2017 Legacy of a Dream Recipient

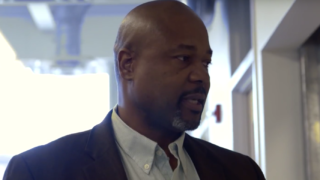

Abel Enrique Núñez, executive director of the Central American Resource Center (CARECEN), will be honored as Georgetown’s 2017 John Thompson Jr. Legacy of a Dream Award recipient Jan. 16 at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

The university presents the award to an inspirational and emerging local leader at the free Martin Luther King, Jr. Let Freedom Ring Celebration, this year featuring awarding-winning singer Gladys Knight.

The award is an integral part of Georgetown’s commitment to helping address key issues in Washington, DC.

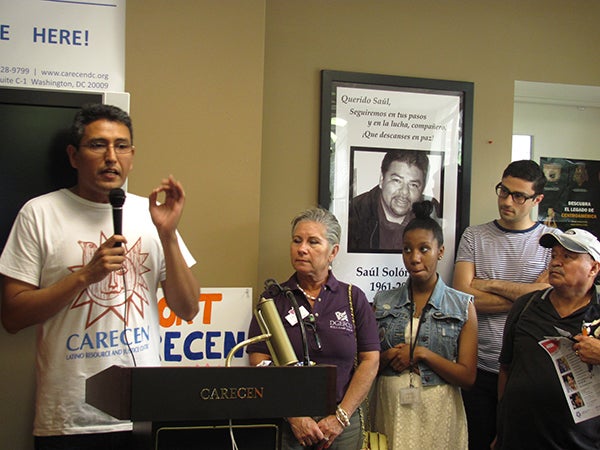

Since 1981, CARECEN has provided a wide range of services for the Washington, DC-area Latino population, including direct legal assistance, housing counseling, citizenship education and community economic development.

“This is a great honor, and I am really humbled to receive it,” says Núñez, who immigrated with his family to America in 1979 from El Salvador and grew up in the District. “CARECEN is poised as an organization to convene the Latino community in the District and facilitate a process to determine a common agenda.”

The Legacy of a Dream Award marks the start of a year’s commitment and sustained partnership with Georgetown that allows winners to leverage the honor for broader recognition of his or her community organization or cause.

Impacting Thousands

As executive director of CARECEN, Abel Núñez has impacted the lives of thousands of children, women and men in Washington, DC’s Latino community by providing essential services.

CARECEN also promotes grassroots empowerment, civic engagement and civil rights advocacy.

“Through his leadership at CARECEN, Mr. Núñez has impacted thousands of children, women and men in our city’s Latino community, providing them with essential services and resources that contribute to their own well-being and help to empower and uplift our entire DC community,” says Georgetown President John J. DeGioia. “We are grateful for the opportunity to recognize his dedicated service with this award.”

Before he took the helm as executive director of CARECEN in 2013, Núñez worked for 13 years at a similar organization in Chicago called Centro Romero.

“He’s task-driven, but he’s also a good communicator and likes to share his knowledge,” says Daysi Funes, Centro Romero’s executive director. “And he is a great coach for the next generation of Latinos. These are qualities that are hard to find.”

Also a native of El Salvador, Funes says she is “proud to know that a Salvadorian, first-generation, would receive such a recognition It’s a confirmation of his work and his commitment to the community.”

Thriving Community

CARECEN also promotes grassroots empowerment, civic engagement and civil rights advocacy.

At CARECEN, Núñez has expanded services to the suburbs surrounding the District, successfully pushed for legislation that allows undocumented immigrants to more easily obtain a driver’s license, and has a list of many other accomplishments.

“I think our most important work is that of integration,” Núñez says. “What we do in essence is ensure that newcomers are able to enter a new society and function in it. Not only just function but thrive.”

“The majority of the clients we see are those that have issues interacting with the U.S. system,” he adds. “Whether it is the local system or the federal system, our role is to empower those participants to be able to engage and strengthen their roles in American society.”

CARECEN has served over 87,000 people throughout the organization’s history at a rate of about 2,500 a year.

Access to Driver’s Licenses

More recently, CARECEN and Núñez worked with Georgetown’s Office of Community Engagement and its Center for Social Justice, Research, Teaching and Service (CSJ) on the difficulty undocumented immigrants have in obtaining drivers’ licenses.

The CSJ conducted research and recommended action, and a new policy – which took effect this past August –now allows undocumented immigrants to more easily obtain a Limited Purpose driver’s license at the DC Department of Motor Vehicles.

Núñez says that prior to the new policy, such individuals had to set up a separate process of appointments and that getting a license could take up to two years.

“We believed that these immigrants should be treated just like any resident in the District of Columbia,” he says.

Among those working on the project with him was his life partner, Diana Guelespe, CSJ’s former director of research and evaluation who now serves as assistant director at the Consortium for Race, Gender and Ethnicity at the University of Maryland.

“We share a lot of values,” Núñez explains.

Immeasurable Contributions

“CARECEN is a critically important voice for Latin American immigrants and all Latinos in Washington, DC at a time when immigration is receiving so much attention nationally,” says Chris Murphy, vice president for government relations and community engagement, who oversees the university’s Office of Community Engagement. “I think Dr. King would be proud to see CARECEN executive director Abel Núñez honored with the Legacy of a Dream Award.”

A full history of CARECEN accomplishments may be found here.

Jorge Granados, CARECEN’s vice president and a member of its advisory board for more than 20 years, says he’s known Núñez for a quarter of a century.

“We as a board are very excited about his performance throughout these last three years as executive director,” says Granados, who has volunteered with CARECEN for three decades. “He has more than reached our expectations, and we are immensely satisfied with the way he has followed through on our vision for the organization. His leadership gives us an optimistic view of CARECEN’s future, and we believe the organization will continue to grow and continue to serve these communities as a result.”

Abel Núñez says he hopes to expand CARECEN’s reach beyond Wards 1 and 4 in the District.

Elevating a Profile

“I think it is a continuation of the elevation of CARECEN’s profile in the city,” says Núñez, when asked how he thinks the partnership will help his organization. “Historically, CARECEN has worked with the immigrant community. And because immigration is a federal issue, it has not necessarily been more intentional about work in the District of Columbia outside of Ward 1 and Ward 4. I really want this award to elevate our work so that we have a bigger footprint and open up relationships in other parts of the city.”

The executive director also says he wants to continue expanding the organization beyond the city’s boundaries and already is doing work in Maryland.

Voice for the Voiceless

CARECEN and Georgetown have similar missions, he says.

“One of the individuals who plays a very important role in organizations like CARECEN is Monsignor (Oscar) Romero, who was a martyr from El Salvador,” Núñez explains. “He was the archbishop of San Salvador who was assassinated in 1980, and one of his themes was ‘You have to be the voice of the voiceless.’ ”

“That is a very Jesuit principle of continual learning but also to be a defender of social justice in civil and human rights,” he says. “I think that CARECEN falls in line with that and that we share that principle in common.”

Georgetown gave Romero an honorary degree in 1978.

Fostering Integration

The Legacy of a Dream awardee says that Latinos currently make up about 10 percent of the District population and he expects that to continue.

Some of the most serious unmet needs of these immigrants, he says, include education and housing.

“We have a community that is coming in already undereducated with limited English capacity and who cannot engage the local, state or federal systems,” says Núñez, who serves as chair of his hometown of Cottage City, Maryland’s government. “So we continue to work on that so that children and their parents can integrate into the U.S. society economically, civically and socially.”

He says gentrification in the city is a problem that continues to affect both Latino immigrants as well as African Americans, and that he grew up in a community without a lot of resources.

“I was shaped by the U.S. and by my experience coming to the capital of the U.S. of the most powerful country in the world,” he says, “but I also lived in a marginalized community during that time. I understood the levers of power that this country has but also the exclusion communities face as a result. I was able to really empathize with the plight of African Americans and understand what they had gone through. I could see the connections to our struggle and also understand that their struggle is my struggle and my struggle is their struggle.”

Building Relationships

With the Georgetown partnership, Núñez says he hopes to elevate CARECEN’s capacity and “build relationships across ethnic lines, across geographic lines south of the (Anacostia) River and across Wards 7 and 8 and to really build those relationships that help strengthen not just the Latino community and not just the immigrant community but the local Washington DC community.”

Isabel Moreno, of El Salvador began receiving help from CARECEN in 2003 when he and other low-income residents faced eviction from a run-down building on Sherman Avenue in Northwest DC.

Núñez, as deputy director at CARECEN, worked with the residents and the building eventually was repaired and converted into a cooperative.

“We were so desperate, and we came to CARECEN for help,” Moreno said through an interpreter. “We saw [Núñez] as a person who understood the needs of the tenants. He was the one who was translating for us when we needed someone to translate for us.”

Moreno said the tenants decided to continue working with CARECEN and also referred the organization to other buildings with similar problems.

“We found that CARECEN helped not only with housing but in many other ways,” Moreno explained.

“We have lengthy relationships with some of our clients, and they come for different reasons over the years, and we serve them in different ways,” Núñez says. “When CARECEN started doing a lot of the housing work, we took a lot of people from being renters to being owners.”

Early Days

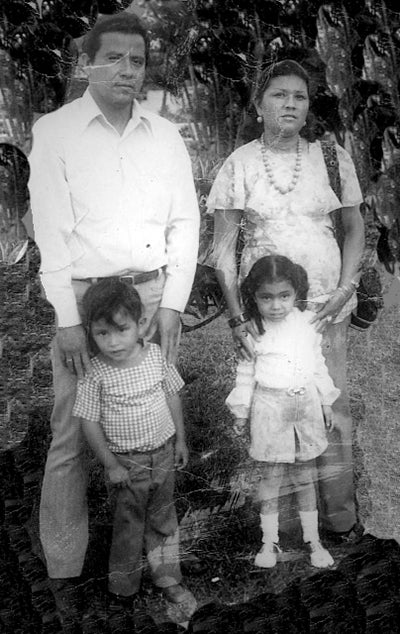

Núñez emigrated from El Salvador to America at the age of 8 with his parents, Abel Antonio and Edith Núñez, and his sister, Ana, in 1979, the same year the civil war began in his native country. He grew up in the District of Columbia near 16th Street, attended Woodrow Wilson High School and worshiped at the Shrine of the Sacred Heart.

“Sacred Heart, where I did my first communion, was the center of religious life then because it was one of the first Catholic Churches that offered a Spanish Mass,” Núñez recalls. “We were a much smaller community at the time.”

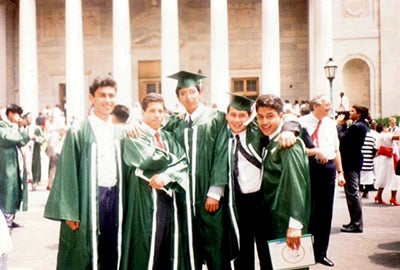

After a couple of years at Montgomery College, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business administration from Hofstra University.

Better Opportunities

His parents came to this country with an elementary school education and struggled to learn English at what later became the Carlos Rosario School for Adults and make a living.

“When they made the decision to come to the U.S. it was primarily for me and my sister,” Núñez explains, “for better educational and economic opportunities.”

He says he was lucky that one of his aunts came to America in the 1960s through the au pair program and by the 1970s had become a citizen and was able to petition for his father.

“In 1979 when the visa was available, the process of petitioning took one year,” Núñez says. “The same process right now for Salvadorans is taking anywhere from five to fifteen years.”

Public Allies

Núñez says his he realized he wanted to work in the nonprofit sector during his service with Public Allies in the late 1990s. During that time, he met Nakeisha Neal Jones, who later became executive director of that organization and won the Legacy of a Dream Award in 2016.

“We’’re a few years older now, but not much has changed,” Neal Jones says. “Abel is a passionate, tireless and skillful organizer and bridge- builder. His leadership has helped many of our neighbors gain citizenship, retain affordable housing and participate in full voice. This kind of leadership is needed to ensure that our city is inclusive and at its best.”

She says Public Allies is “extremely grateful for the yearlong partnership with Georgetown.”

“It has strengthened our communications, provided resources to strengthen pathways to higher education and employment after the ally program, opened up professional development opportunities for our staff and raised our overall profile,” Neal Jones says.

Núñez says his time in Public Allies, when he worked at the Latino Civil Rights Task Force, shaped his thinking.

“That is when I knew that I wanted to work in nonprofit, in community work,” he says. “It was this incredible experience that helped define me.”