Georgetown held a service in remembrance of the 272 children, women and men enslaved and sold by the Maryland Province of Jesuits in 1838. The names of the 272 individuals will be read aloud during the 5 p.m. event in Dahlgren Chapel.

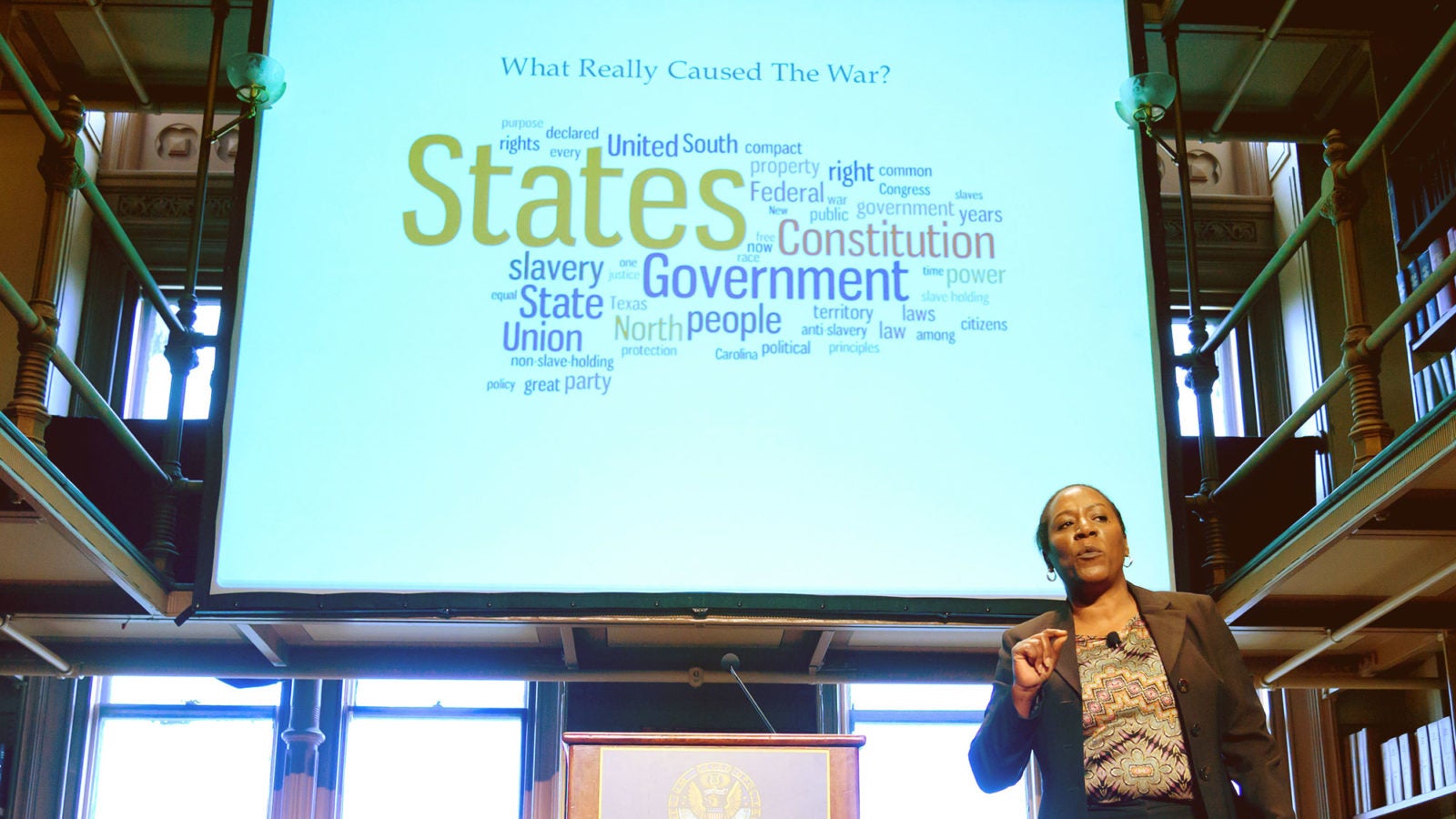

“Here’s the thing about the past,” said Christy Coleman, CEO of the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia, who spoke April 15 at Georgetown. “If we really want to learn from it, we have to be honest about it, and we have to accept it on its terms. That’s where the real lessons come from.”

Coleman talked about the importance of thinking critically about the information we read when it comes to history. She said “we can no longer afford to lie about the American past” as it relates to historical attempts to distance slavery as a reason for the Civil War.

Jeremy Alexander, a descendant of the 272 enslaved individuals, participated in yesterday’s events with his wife, Leslie, and son, Jesse.

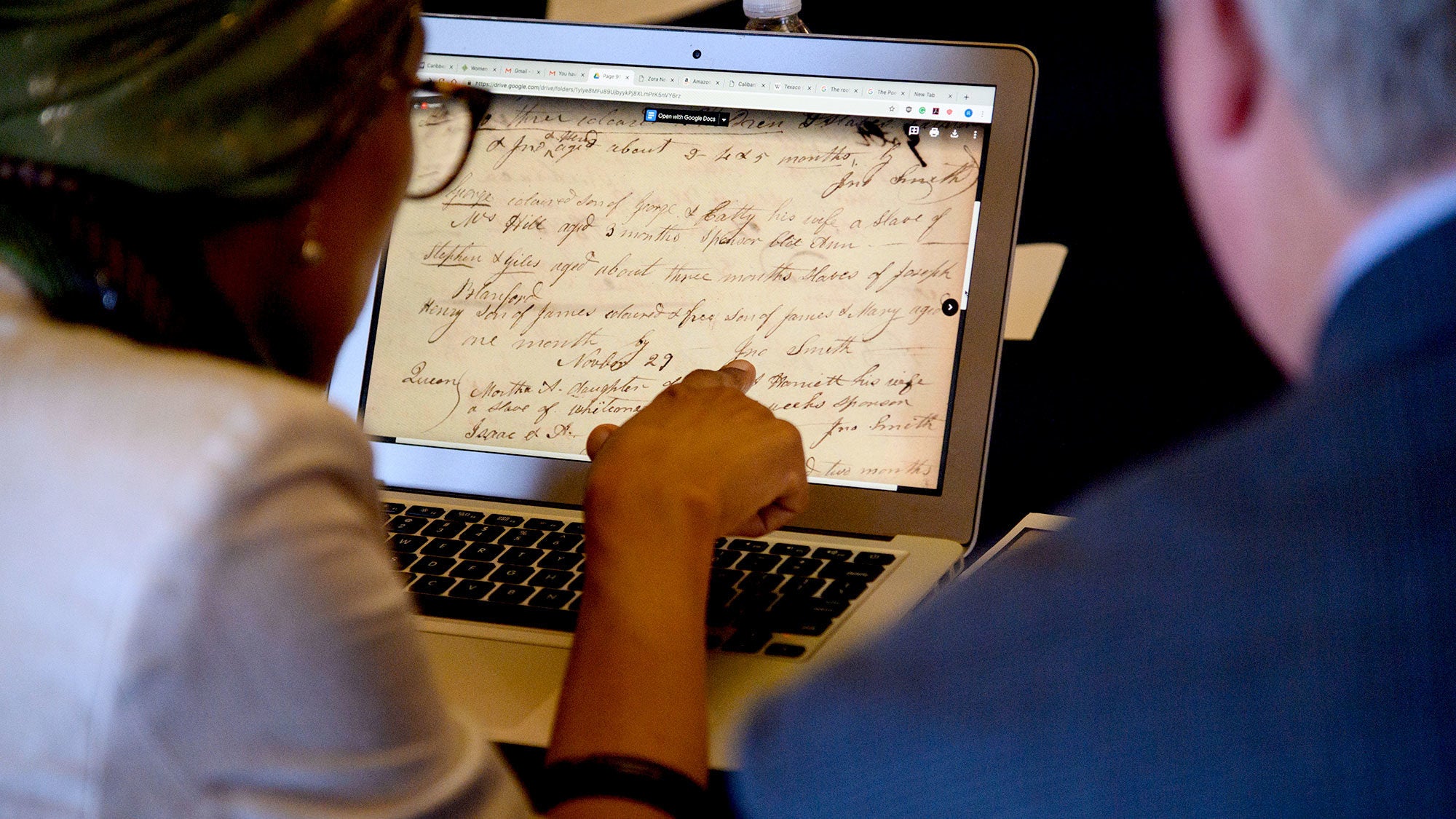

Earlier that day, he and his family joined other descendants, faculty, staff and students on campus to transcribe a sacramental register of Catholic baptisms, marriages and burials related to the enslaved and free people of color around the White Marsh Jesuit plantation in Bowie, Maryland for the Georgetown Slavery Archive.

Descendants were also invited to participate in the event remotely.

“These documents prove that the priests acknowledge the enslaved people had souls, yet they kept them enslaved and sold them,” said Alexander, who works in the Office of Technology Commercialization at Georgetown. “Most of my family members remain as Catholics today due to my ancestors being baptized into the Catholic faith by these priests.”

Alexander remains Catholic because of his strong belief in God and said he’s looking forward to seeing the transcriptions continue so he may learn the date of births and other information about his ancestors – Christine West, Anna Mahoney Jones and her children, Arnold Jones Jr. and Louisa Jones.

“One of the issues with these archival materials is that much of it is handwritten and difficult to read,” said Slavery Archive curator Adam Rothman, a professor of history at Georgetown. “That’s why we decided to sponsor an event to transcribe these particularly important and interesting records.”

Lynn Nehemiah, also a descendant, attended the transcription event with her teenage son, August Matthews.

“My third great grandmother, Louisa Mahoney Mason, was the last of the slaves to be freed by the Jesuits in 1864,” Nehemiah explains. “It’s really important for me and my son – I took him out of school to be here today to be able to honor the legacy of the descendants.”