Title: Georgetown Conducts Groundbreaking Dyslexia Research

Georgetown University Medical Center researchers find differences in how dyslexia looks in male versus female brains and determine that changes in the brain’s visual system don’t cause dyslexia.

University researchers are conducting groundbreaking research on dyslexia – recently unhinging a commonly held belief about its cause and determining that the reading disorder looks different in the brains of males versus females.

Georgetown University Medical Center (GUMC) researchers published in the journal Neuron this month that differences in the brain’s visual system don’t cause dyslexia, but instead are more likely to be a consequence of the learning disability.

The group reported in the journal Brain Structure and Function last month that women have less gray matter volume in areas involved in sensory and motor processing. The researchers say this is very different from the observations made in males with dyslexia – they have less gray matter volume in the language processing part of the brain.

Males vs. Females

Guinevere Eden

Guinevere Eden, director of the Center for the Study of Learning and a past president of the International Dyslexia Association, says “females have been overlooked” in dyslexia because the disorder is two to three times more prevalent in males.

“It has been assumed that results of studies conducted in men are generalizable to both sexes,” Eden explains. “But our research suggests that we need to tackle dyslexia in each sex separately to address questions about its origin and potentially, treatment.”

Previous work outside of dyslexia demonstrates that male and female brains are different in general, adds the study’s lead author, Tanya Evans (G’13).

“There is sex-specific variance in brain anatomy and females tend to use both hemispheres for language tasks, while males use just the left,” Evans says. “It is also known that sex hormones are related to brain anatomy and that female sex hormones such as estrogen can be protective after brain injury, suggesting another avenue that might lead to the sex-specific findings reported in this study.”

Visual System

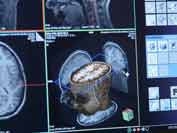

A girl acclimates to the MRI environment, where male and female subjects are given tasks to complete for a dyslexia study.

Eden and her colleagues were the first to publish brain scans acquired with fMRI in dyslexic participants in 1996. She says her most recent study is consistent with her earlier brain imaging research, which showed differences in a specific stream of the visual system.

“The new study doesn’t discount the presence of a specific type of visual deficit in dyslexia, but shows that the deficit in the visual system is not the cause of the reading disability,” Eden explains. “Instead, it is most likely the result of people with dyslexia reading less often than their peers.

“The researchers used functional MRI to study children of the same age with and without dyslexia to demonstrate the difference, and then showed the difference not to be there when the dyslexic children were compared to younger kids with the same reading level as the dyslexic kids,” Eden adds. “This group looked similar to the dyslexics in terms of brain activity, providing the first clue that the observed difference in the dyslexics relative to their peers may have more to do with reading ability than dyslexia per se.”

The children with dyslexia then received a reading intervention. After intensive tutoring of phonological and orthographic skills, the children made significant gains in reading, which was reflected by increased activity in their brains’ visual systems.

Further Implications

The research team uses structural brain scans to examine gray matter volume differences in groups of male and female subjects with and without dyslexia.

The researchers point out that these findings could have important implications for health professionals.

“Early identification and treatment of dyslexia should not revolve around these deficits in visual processing,” says Olumide Olulade, a GUMC post-doctoral fellow and that study’s lead author. “While our study showed that there is a strong correlation between people’s reading ability and brain activity in the visual system, it does not mean that training the visual system will result in better reading.

“We think it is the other way around,” he says. “Reading is a culturally imposed skill, and neuroscience research has shown that its acquisition results in a range of anatomical and functional changes in the brain.”

The researchers add that their research can be applied more broadly to other disorders.

“Our study has important implications in understanding the etiology of dyslexia, but it also is relevant to other conditions where cause and consequence are difficult to pull apart because the brain changes in response to experience,” Eden explains.