This story is part of Georgetown Faces, a storytelling series that celebrates the beloved figures, unsung heroes and dedicated Hoyas who make our campus special.

By Elizabeth Terry

Yi Song (L’10) is on her third go-round with Georgetown University.

The Beijing native first visited the Hilltop as a 22-year-old exchange student, spending a summer studying political economy at Georgetown.

She fell in love with DC and returned to Georgetown a few years later, after having practiced tax law in China, to earn an LL.M. — a specialized master’s degree in law for those who’ve already completed a J.D. or its equivalent. She then worked for a decade in private practice before finding her way back to her alma mater as an instructor and administrator.

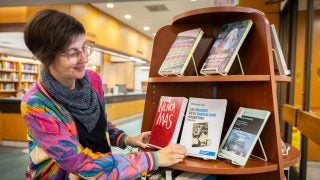

Song is now the executive director and adjunct professor of Graduate and International Programs at Georgetown Law, where she advises LL.M. students on their academic and career plans, and teaches in the LL.M. Summer Experience, a special summer orientation program for incoming Georgetown Law LL.M. students.

At Georgetown Law, Song has found a calling in helping fellow foreign-born students figure out a way to use their multilingualism and legal training to build fulfilling careers, just as she has. In 2023, she launched the Masters of Laws Interviews Project, an oral history series that features conversations with multilingual and internationally trained lawyers on their career paths.

“Language is the only homeland. I love living in English, in a second language, which is really a funny feeling. How can you feel at home in a second language? I just knew that when I was in China, it was like how in a Sally Rooney novel, characters are kind of waiting for life to begin,” Song says of her own approach to embracing what she calls being “linguistically diverse.”

Read on to learn about how her youthful ambitions have come alive in her current work and life.

How I came to love law (even though it wasn’t my first career choice): My passion was to study English, and I really wanted to go to Beijing Foreign Studies University, which has a special program for language training. My initial intention was to major in journalism because my role model in high school was Yang Lan. She’s like the “Chinese Oprah,” she interviewed all the U.S. presidents, and she has her own media company and went to the college that I went to. And storytelling runs in my family, we’d like to think that we all have very good memories.

But journalism was a hard major to get into, and after I took the college entrance exam, it wasn’t ideal. So I thought law would be the practical choice. As it turned out, in the legal practice, there are so many stories. Nobody calls a lawyer when everybody’s happy. We are only in the room when there’s a problem. Each character enters the stage with their own tension and drama. So I kind of found what I was looking for initially in law.

What it was like having Georgetown as my introduction to the U.S: I was 22, in a summer program sponsored at the time by Georgetown University and this organization called the Fund for American Studies. They had an equivalent program in Asia at the University of Hong Kong, so I did the Hong Kong program the year before, then studied political economy in Georgetown and did an internship with an NGO. That experience made me fall in love with DC. It is just beautiful, and it’s so clean and there are free museums.

Studying with professors at Georgetown, putting on a nice dress and getting on the Metro and pretending to “go to work” — it was really charming. And I made so many friends. I met my husband in the program! He is from Beijing, too, and his family moved to Michigan when he was 10. I just knew that I wanted to come back in some capacity someday.

How I ended up becoming a talk show host after all: Our international students all have the same questions as I did when I was looking for jobs: How do I get a job as an international law student? So I had an idea for a project to amplify the voices of linguistically diverse lawyers, and particularly international lawyers who came to the United States for a law degree and stayed — either they developed and established their U.S. legal practice or they have a global practice with a U.S. component.

This talk show kind of format, just having a conversation, that’s really my favorite format of narrative. I have watched a lot of talk shows ever since the days when I was learning English. Perhaps there’s also the inspiration from Yang Lan, the “Chinese Oprah.” So that was really the seed of the project.

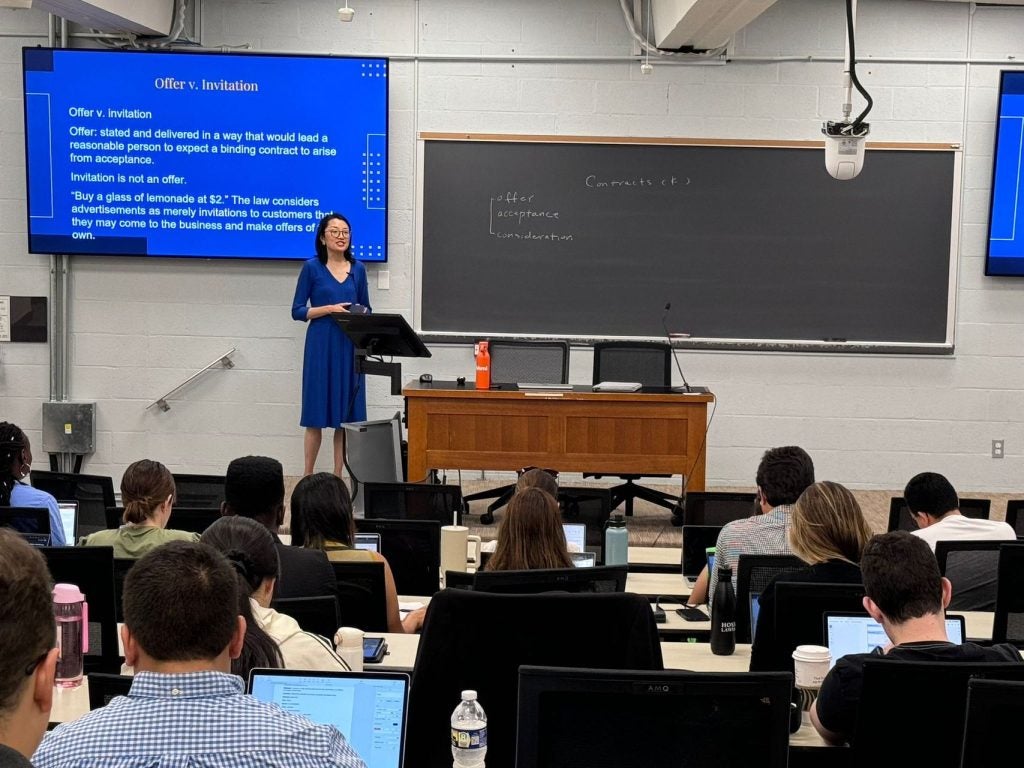

Then as a test run, I asked my friends who are practicing lawyers to get on Zoom and talk to my students for 15 minutes at the U.S. Legal Research, Analysis and Writing class I teach. Students appreciated the opportunity to speak to a practicing lawyer who was just like them a few years ago. So I kept doing it, and I thought, if Georgetown students like it, then why not make it available on a bigger platform? In early 2023, I launched Masters of Laws Interviews Project, which is about to launch its fifth season.

What I hope my students get from the conversations: Students tell me, “Oh, my English is not very good.” I felt the same way, too, when I came to the States. I felt like I should lock myself in a room and practice until I sounded like Julia Roberts to go on job interviews. That’s why I wanted to have the audio component in the project.

I want people to listen to these accomplished international lawyers, who are “BigLaw” partners, senior counsel for multinational corporations, and law professors who speak English with a charming accent. Many lawyers I interviewed speak multiple languages fluently, and it doesn’t stop them from passing the bar. It doesn’t stop them from getting the job that they wanted. It doesn’t stop them from practicing law in the United States. Though people tell me they have to battle different biases because they’re linguistically diverse.

So I want to send a message to students: don’t feel like your background is a deficit. Maybe this is something that the employers need, a special skill set that you have. If she or he did it, you can, too!

The pros and cons of practicing as a bilingual, bicultural lawyer: When I went back to China for the first time as a U.S.-licensed lawyer, the partner was like, “OK, you should do the presentation in Chinese, so you connect with the investors and potential clients. And the investors were like, “Oh, but we want a real American lawyer.” We regrouped in the second meeting, and I presented in English. And the investors were like, “Why are you speaking English? You forgot how to speak Chinese? Why are you so pretentious to pretend that you’re not one of us?”

Language is one thing, but other times it’s really more about cultures. For example, in Chinese culture, if we don’t like something, we usually don’t go straight out to tell you no. I’ve seen tension built up and disputes initiated due to the misinterpreted intent. That kind of cultural miscommunication is not about language. It is not something ChatGPT would understand. At least not now. That’s more about cultural norms, which internationally trained lawyers are more attuned to.

What it’s like raising a bilingual child: Our son is five, and we speak both Chinese and English at home. Sometimes my parents are here to take care of him, and we all speak Chinese. Then I heard all these horror stories from stand-up comedians who are immigrants and they were dropped off at daycare and didn’t speak a word of English. So I started to speak English to my son, just to prepare him for daycare.

The first word that comes to mind when I think of Georgetown: Home. I think it’s really where everything begins for me and my journey in America. I found lifelong friends, partners at work and in life, and mentors and a community. During the 10 years I was away from DC, I would miss it a lot. Now that I’m really here, I don’t take it for granted.