Title: Global Anthrax Risk Areas Include More Than 60 Million People

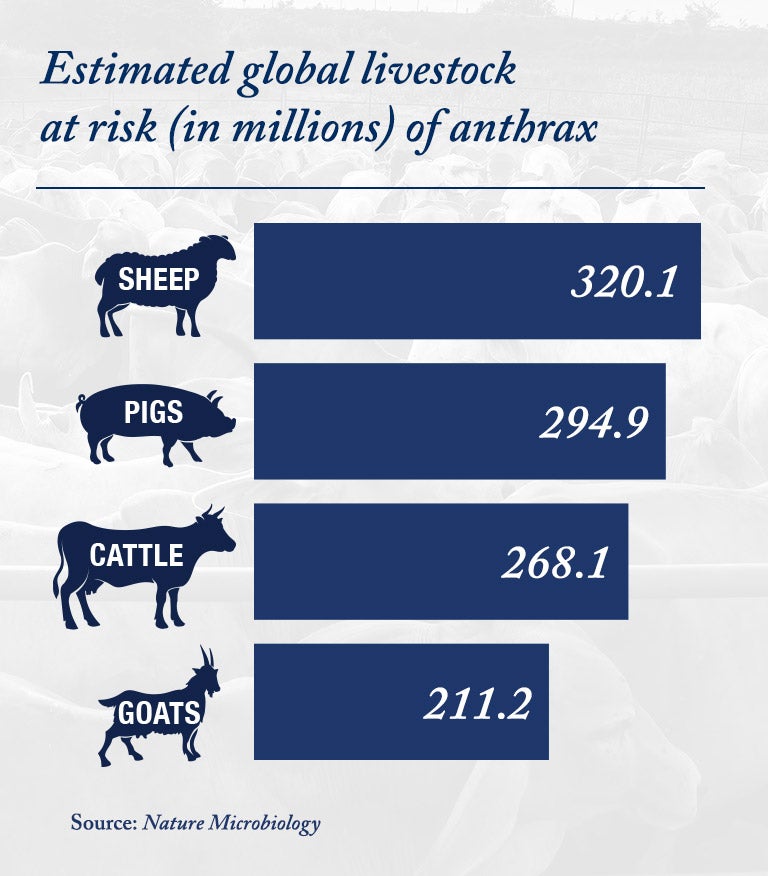

The first global survey of anthrax risk to humans and livestock, published today in Nature Microbiology, estimates that approximately 63 million livestock keepers live within regions vulnerable to the spore-forming bacterial disease.

The first global survey of anthrax risk to humans and livestock, published today in Nature Microbiology, estimates that approximately 63 million livestock keepers live within regions vulnerable to the spore-forming bacterial disease.

Colin Carlson, a Georgetown biology department postdoctoral researcher, is first author on the paper, a collaboration with other universities using a grant from the National Institutes of Health to the University of Florida.

The paper estimates that a total of 1.83 billion people live at risk within such regions, including rural areas in Eurasia, Africa and North America, but that most face essentially zero occupational hazard.

‘Part of Life’

“When we talk about anthrax outside of science, we talk a lot about anomalies, like spores coming out of the permafrost,” Carlson says. “But anthrax is a part of life for farmers and pastoralists on every continent. Our team has been mapping this country by country for over a decade. But this is the first time we can stitch all that together, and see the whole world. For us, that’s very exciting.”

In North America, about 39 million livestock, primarily cattle, live in anthrax-endemic areas.

But livestock vaccination and careful control minimize the threat to humans, he says.

“In a lot of parts of the world, vaccine coverage is fairly high,” Carlson explains. “History plays a big role, like in the former Soviet Union, which had actually eliminated anthrax for a few decades. That helps us understand the world we live in now, and explain why the burden of anthrax is especially high in a few countries.”

Reevaluating Vaccination Rates

Jason Blackburn, senior author on the paper who directs the Spatial Epidemiology & Ecology Research Laboratory at the University of Florida, notes that the reported vaccination rates are high, but not where the human population at risk is the highest.

“Ultimately, we show that vaccination rates are limited to national reports that are out of sync with populations at risk, but we can’t map vaccination at the same scale as our model,” Blackburn says. “Our model allows us to re-evaluate if vaccination rates are appropriate in areas of highest risk.”

More to Learn

The research team for the paper, in addition to Georgetown and University of Florida, includes scientists at the universities of Maryland, Virginia Tech, Louisiana State as well as the University of Saskatchewan, the University of California, Berkeley, and researchers in Australia, China and Azerbaijan.

The paper notes that worldwide, there are an estimated 20,000 to 100,000 cases of anthrax a year.

That majority of cases of anthrax, caused by a bacterium called Bacillius anthracis, involve cutaneous exposure (often from butchering and eating contaminated meat) that is non-fatal, the paper notes, with the much rarer, deadly cases involving respiratory exposure.

Also noted in the paper is an “anthrax-like” disease that the researchers say could become a serious problem in the future.

“The science of anthrax has changed and grown a lot in the last few years,” Carlson says. “We’re still constantly learning new things about the biology and ecology of these bacteria. We’re taking a big step forward today, but there’s still a lot left to learn before we see the whole picture.”