Title: Guggenheim Fellowship Aids Research on Stalinism, German WWII Occupation

Georgetown professor Michael David-Fox wins a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship for a book project on how the Soviet system and the WWII German occupation regime intertwined in the Smolensk region.

Michael David-Fox, a Georgetown professor of history and foreign service, has won a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship for a book project examining how the Soviet system and the WWII German occupation regime intertwined in the Smolensk region.

Smolensk was a Russian region of the U.S.S.R. that was invaded by Nazi Germany in July 1941 and reincorporated into the Soviet Union after September 1943.

“Both sides were gathering information on the other,” explains the professor, a historian of modern Russia and the U.S.S.R. “I’m going to show how the experience of Stalinism, the genocidal violence of the Germans and the Holocaust on Soviet territory and the German occupation of a huge swathof Soviet territory were all entangled.”

One of 173

David-Fox says the three topics have often been studied separately, but few researchers work as he does on all of them, using primary sources in both Russian and German.

He is one of only 173 of3,000 applicants to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship this year from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation,which makes awards to scholars, artists and scientists.

United States Senator Simon Guggenheim and his wife established the foundation in 1925 as a memorial to their late son.

The most recent Georgetown history professor to receive a Guggenheim was Michael Kazin in 2003.

Sustained research

David-Fox says his first reaction to getting the Guggenheim was relief.

“Georgetown is an intensive teaching institution and a research university at the same time, and I sit on my share of committees in the School of Foreign Service and the history department,” he says. “It’s hard to do sustained research without some time off, which will allow me to focus on the library and archival work.”

David-Fox will use the Guggenheim to conduct additional research in Moscow and Smolensk, at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum archives in Washington and at the National Archives in Maryland.

“I first started thinking about this project as early as 2010, when I took a course for university professors at the Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the U.S. Memorial Holocaust Museum,” says David-Fox, who holds a Ph.D. in history from Yale. “I learned that about 90,000 pages of microfilmed archival material from Smolensk during the war had recently become available at the Holocaust Museum archive.”

Smolensk Archive

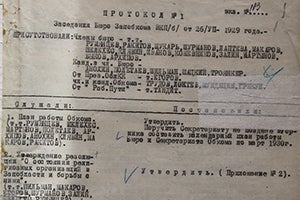

He also has examined the Smolensk Archive, which comprises documents the Soviets failed to evacuate before the Germans arrived. The archive ended up in the United States and eventually was returned to Russia in the early 2000s.

“More than one generation of historians in my field worked with materials from the Smolensk Archive,” David-Fox says. “But then all the former Soviet archives opened up after 1991 and pretty much everyone in the field forgot about Smolensk.”

Now, he says, the “vastly more comprehensive” documentation available in both Moscow and Smolensk will help him finish the book project.

Life Stories

David-Fox, who has visited Russia at least 30 times and lived there the early 1990s, was one of the first foreign researchers to work with Communist Party archives during the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Since 2013, he has served as a scholarly advisor at one of Russia’s most international universities, the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, and therefore spends about two months in Russia every year.

His forthcoming book will humanize the traumatic decades of the 1930s and 1940s through individual life trajectories and include not just the city of Smolensk, but the oblast – or region –that is about the size of Belgium, he says.

“But wrapped around those life stories, including those of local-level and regional-level political figures and ‘ordinary’ people, is a much bigger archival investigation into how the Soviet system and the German occupation regime worked on the level of the region,” David-Fox says. “My main avenues of investigation encompass ideology, administration and political violence.”

Smarter Generation

A prolific author, the professor’s latest books include

A prolific author, the professor’s latest books include Showcasing the Great Experiment: Cultural Diplomacy and Western Visitors to the Soviet Union, 1921-1941 (Oxford University Press, 2012) and Crossing Borders: Modernity, Ideology, and Culture in Russia and the Soviet Union (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015), which is now under translation into Russian and won the 2016 Historia Nova Prize for Best Book in Russian Intellectual and Cultural History.

Also the author of two other books, nine edited volumes, 12 edited special theme issues of journals and more than 45 articles and chapters on Russian and Eurasian history, he describes the United States-Russian relationship as “one of the most dangerous situations in a long time between our two countries,” and contends that cultural and academic exchanges and high-level scholarly cooperation are more important today than ever.

“There has accrued an unmistakable and sometimes shocking lack of expertise on Russia in the United States today,” the professor says. “After 1991 Russia was for a long time essentially downgraded in importance and Russian studies has been underfunded for a long time. A deficit of expertise and linguistic competence is now a fact of life in a number of academic fields and branches of government.

“I believe the School of Foreign Service and the history, and government departments in particular, have an important role to play in addressing this problem,” he adds. “We have our task cut out for us in training a new, larger and smarter generation of experts and practitioners who know the languages and cultures of Eurasia.”