As a young girl, Karah Knope remembers her parents coming home from their family-owned bookstore with science experiment books and crystal growing kits.

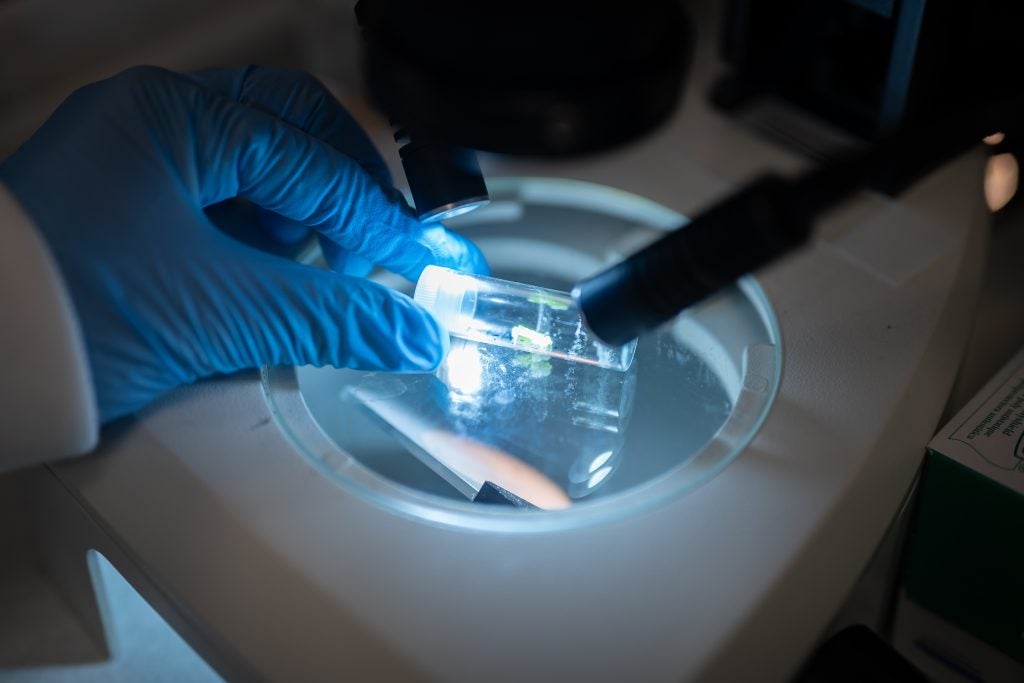

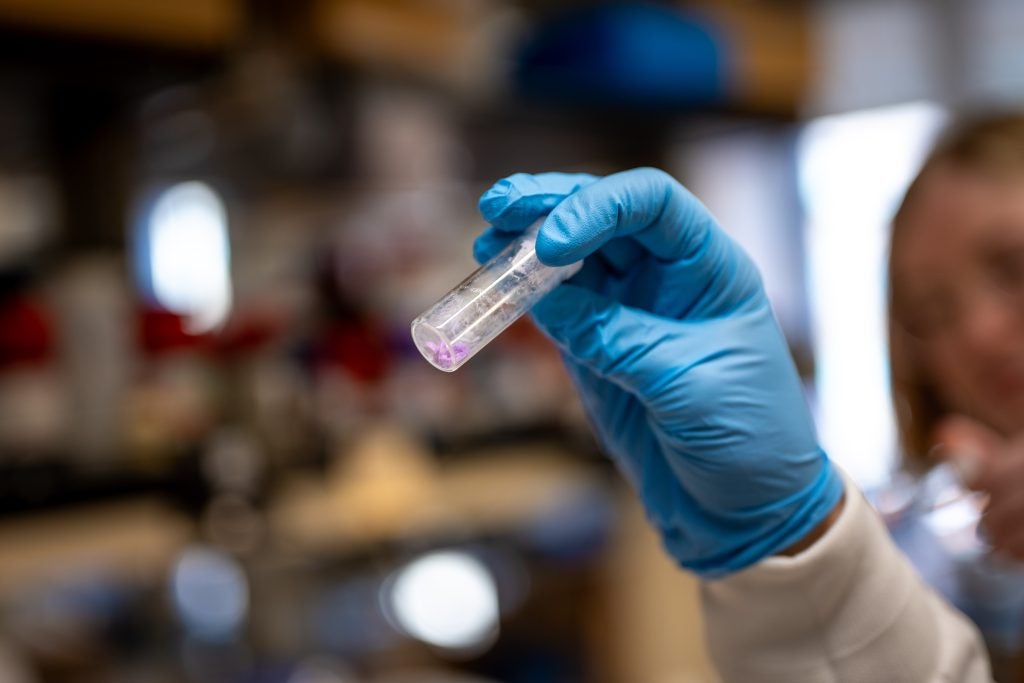

She was fascinated by the crystals — an interest that continued through grade school.

For every science fair, she would always produce a crystal garden.

“I don’t know if it’s the color. I don’t know if it’s the faces. I don’t know if it’s the symmetry. I don’t know what does it for each person, but there are a lot of people who get excited about crystals,” she said. “I think they’re beautiful.”

While Knope can’t pinpoint what about crystals captivated her years ago, they’ve held her attention since.

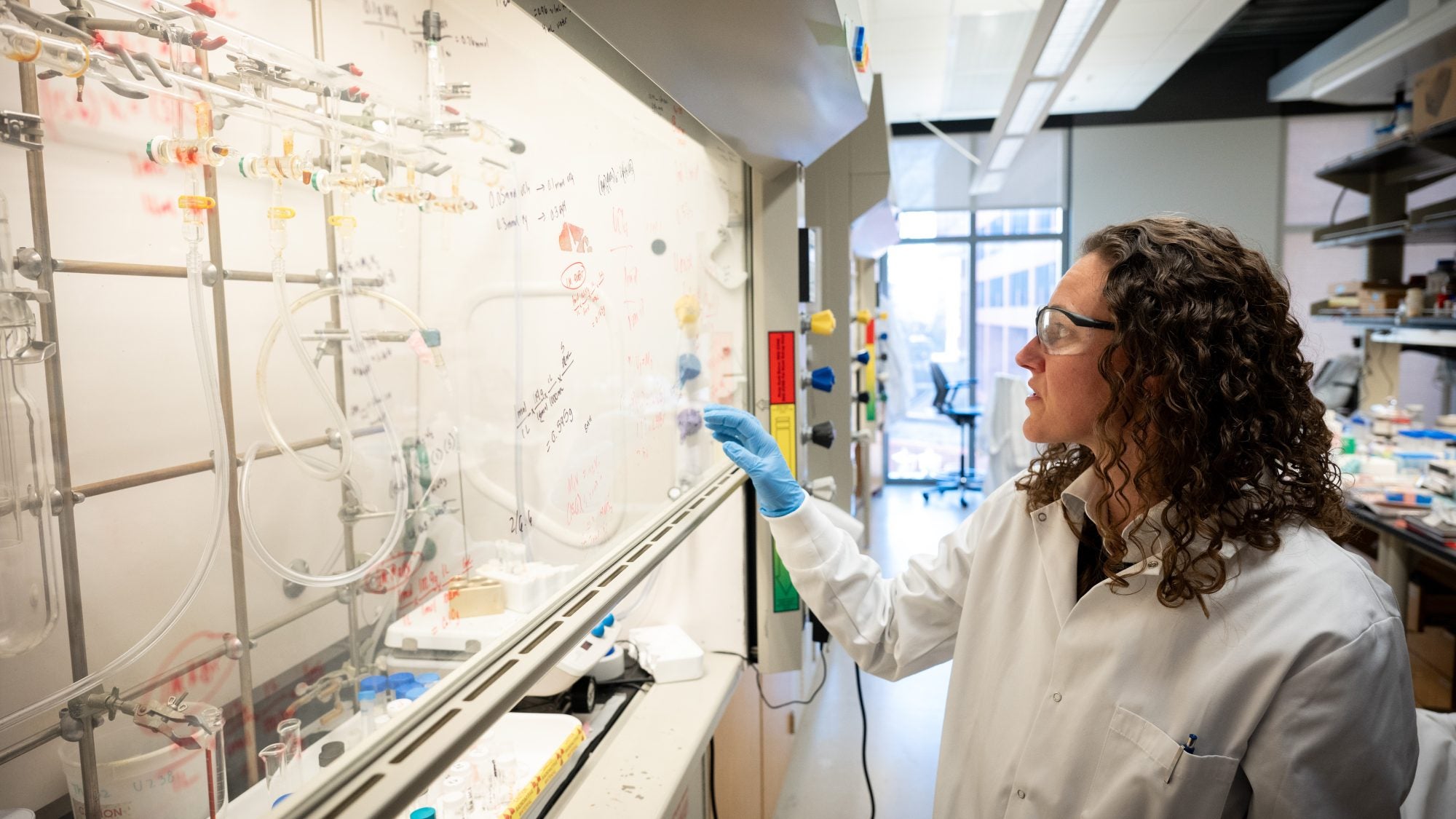

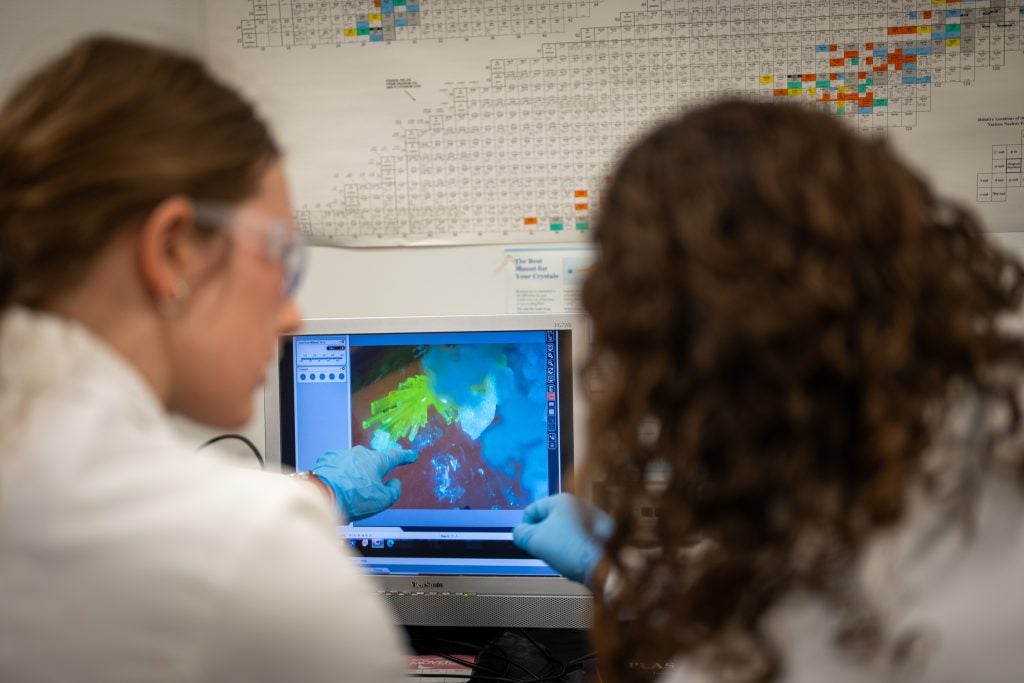

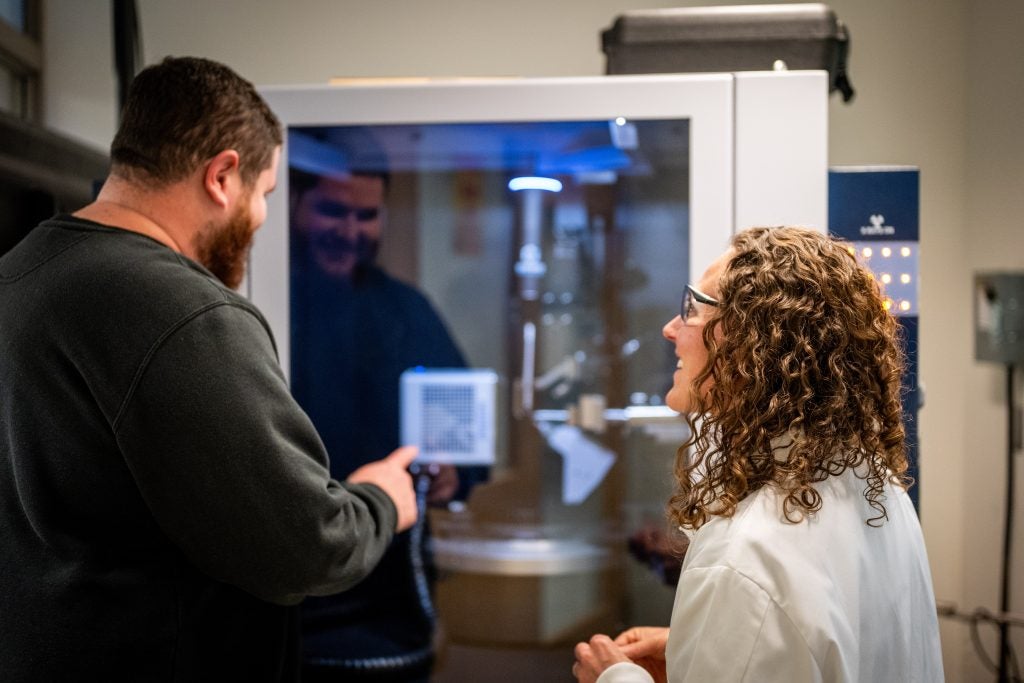

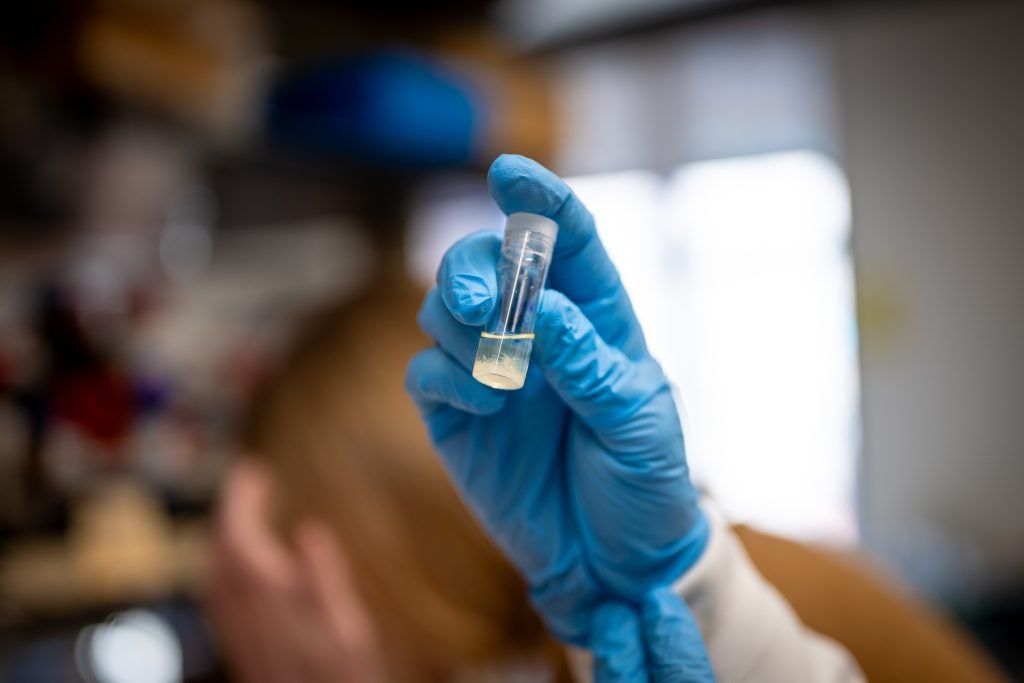

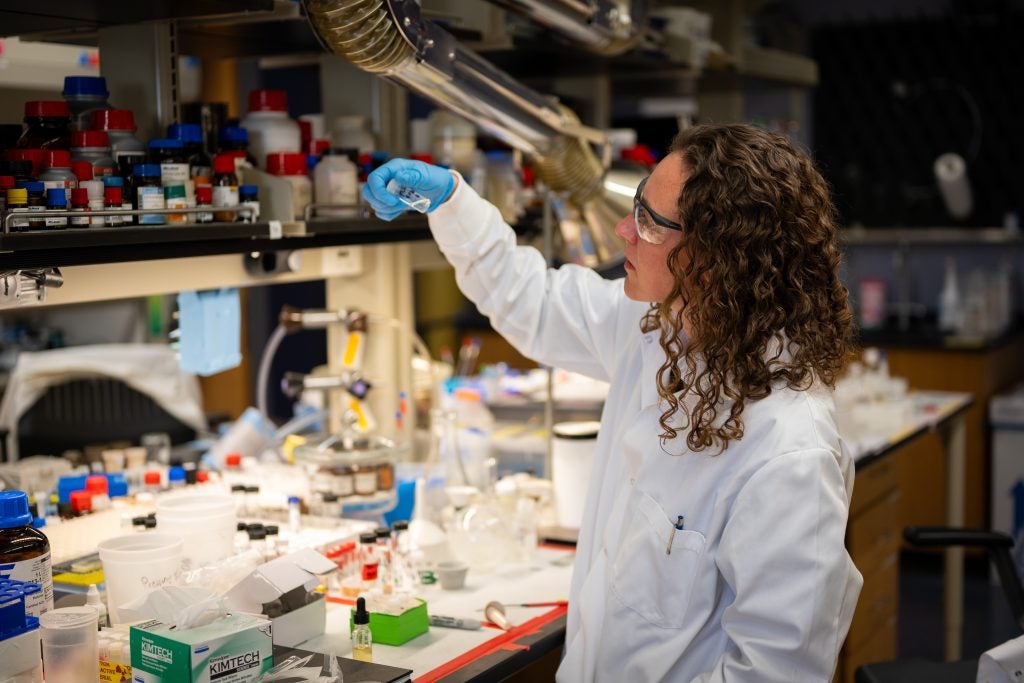

Knope is a Provost’s Distinguished Associate Professor in the College of Arts & Sciences. As a chemistry professor, she still grows crystals. But she’s no longer growing crystals in her childhood living room. She runs a university lab where she studies inorganic chemistry and its applications to energy and sustainability.

On the side, she’s also invested in inspiring the next generation of scientists to be just as fascinated by crystals as she is.

Discovering Her Research Niche

Knope started as a biology major at Lake Forest College, but it didn’t take long for her to find her calling in chemistry.

One day during a general chemistry lab, her professor approached her with an add/drop form and told her that she wasn’t a biology major but a chemistry major.

Knope got the hint.

“I was young and kind of impressionable,” she said. “I said, ‘Well, I guess if he thinks I’m good at chemistry, I’m going to switch.’”

During her junior year, Knope dived deep into research and worked with the same chemistry professor. The project?

Growing crystals.

“When I figured out I could do that, I was hooked,” Knope said of when she realized growing crystals could extend beyond science experiments for children.