Title: Georgetown Continues Engagement with Descendants, Historical Relationship to Slavery

Georgetown’s steady engagement with its historical ties to slavery has included teach-ins, forums and meetings that involve descendants, university leaders and faculty members.

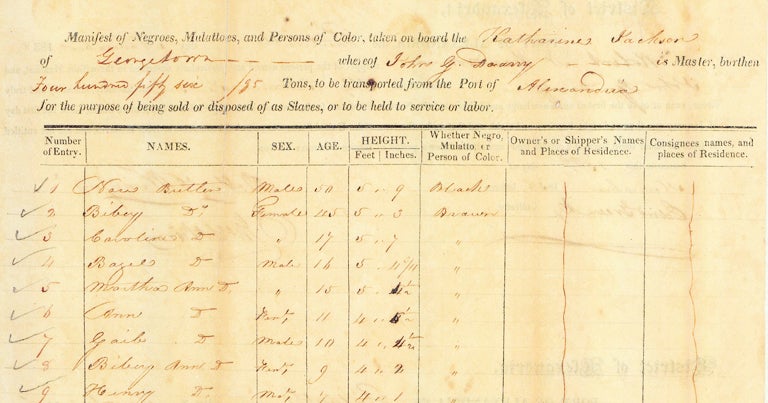

Onita Estes-Hicks learned in 2004 that she was a descendant of Nace and Biby Butler, two of the 272 enslaved people who toiled on southern Maryland plantations before being sold by Jesuit priests in 1838.

But another tragedy, that of Hurricane Katrina, kept Estes-Hicks’ research from advancing for at least five years.

Before the storm, her niece, Patricia Bayonne-Johnson, also a descendant of the Butlers, had been tracking the family genealogy before getting ready for a family reunion in New Orleans. She learned that the272 were largely taken to plantations in Louisiana in the sale, a portion of which went to resolve the university’s debts.

“[My niece] sent the information that she had gotten from the genealogist and I Googled it,” says Estes-Hicks. “Much to my surprise up popped the long story of [Georgetown Jesuit Thomas] Mulledy and his involvement.”

But the research sat in files when the devastating hurricane blew through Louisiana in 2005.

“Everything fell apart then because we lost about 12 homes in New Orleans,” she recalls. “We actually didn’t get people settled back in Louisiana until about 2010.”

APRIL 18 EVENTS

Later, she and her niece were able to begin their research again. And last year, she and family members visited Georgetown to see the sale documents with their own eyes.

Estes-Hicks, her niece, and other descendants are among those planning to attendpublic events at Georgetown on April 18 that will honor the people who came before them and continue to confront the legacy of slavery.

The event follows the April 17 celebration of D.C. Emancipation Day 2017 that will commemorate the end of slavery in the District of Columbia on April 16, 1862. The event is being held a day late this year because of Easter.

A “Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope” as well as the dedication of two buildings on campus previously named for the priests involved in the sale, will take place at Georgetown on April 18.

Descendants were invited to be part of a Georgetown delegation to the United Nations’ commemoration of the International Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade on March 24.

Georgetown United Nations Delegation

The April event is part of a continuing engagement initiative with descendants of the enslaved people and the legacy of slavery.

The university invited members of the Hicks family and other descendants to attend the Let Freedom Ring! celebration at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts on Jan.16 that honored the legacy of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

The annual event is a joint effort of Georgetown and the Kennedy Center, and includes the awarding of the university’s John Thompson Jr. Legacy of a Dream Award.

Later that month, descendants, including those who are a part of the GU272 Descendants Association, attended Georgetown’s Jan. 24 honorary degree ceremony for Lonnie Bunch, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

On March 24, Estes-Hicks will be part of a Georgetown delegation attending a commemoration at the United Nations in honor of the International Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Acknowledging and Recognizing

The university’s engagement with its historical relationship with slavery has been ongoing since 2015, when President John J. DeGioia created a Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to make recommendations about how best to acknowledge and recognize that relationship.

Among the recommendations in the report, released on Sept. 1, 2016, was a call to rename buildings named after Jesuits involved in the sale for Isaac Hawkins, the first enslaved individuallisted in documents related to the 1838 sale, and Anne Marie Becraft, a free woman of color who established a school for Catholic black girls in Georgetown.

The buildings, named Mulledy and McSherry, were temporarily renamed Freedom and Remembrance Halls in 2015 and will be permanently renamed on April 18.

The report also recommended that the university apologize for the sale as well as engage with the descendants of the 272 enslaved women, children and men.

DeGioia also committed in September to giving descendants the same care and attention in the admissions process as children of faculty, staff and alumni.

The recommendations were announced in a livestreamed event at Georgetown.

Academic Research

The 1838 sale has not been unknown to the Jesuits or to the university.

The working group report pointed out that articles about the sale can be found in the Jesuit publication Woodstock Letters, from its inception in 1872 until it ceased production in 1969.

A Georgetown master’s thesis titled “The Slaves of the Jesuits of Maryland,” written by Peter C. Finn, S.J., was written in 1974 and has been available at the university’s Lauinger Library since it was completed.

The materials for an article called “Splendid Poverty: Jesuit Slave Holdings in Maryland, 1805-1838” by then-Georgetown history professor R. Emmett Curran, were presented at a 1981 joint meeting of the American Historical Association and the American Catholic Historical Association.

In the 1990s, under the direction of Georgetown professors, the university’s American Studies Program created the Jesuit Plantation Project, which for almost two decades provided detailed digital documents relating to slaveholding, including diaries, financial records and business correspondence.

The web pages are now maintained on the Georgetown Slavery Archive, created last year, which also contains numerous digitized documents, including the 1838 bill of sale.

Meeting Descendants

In keeping with the working group report’s recommendations, DeGioia and other university representatives have met with many descendants in their homes, in cemeteries where their relatives are buried and at other venues.

In turn, these descendants have been welcomed on campus for discussions, events and visits to Georgetown’s Special Collections to view documents related to Jesuit slaveholding and their ancestors.

Like many universities, Georgetown has been involved in an emotional journey to grapple with a past that DeGioia has said represents “moral failings” and the racial injustice that persists today as a result of the legacy of slavery.

Other universities that are studying their histories and involvement with slavery include Yale, Brown, Harvard, Rutgers, Columbia, Dalhousie, Virginia, William & Mary, Virginia Military Institute, Hollins, Wake Forest, North Carolina, Mississippi and Sewanee: The University of the South.

In the summer of 2016, DeGioia began meeting with descendants of the enslaved people who were sold in 1838.

One of the first visits involved a June meeting in Spokane, Washington, between DeGioia and Bayonne-Johnson, who is believed to be the first descendant to discover details of her ancestry through Georgetown’s Jesuit Plantation Project.

It was through that project that Bayonne-Johnson found her family ties to Maryland, the Jesuits and Georgetown.

A Beginning

The June visit between DeGioia and Bayonne-Johnson is detailed in a story in The New York Times by Rachel L. Swarns, who has written extensively on the topic and is writing a book about the 1838 sale.

“He asked what could he do and how could he help,” Bayonne-Johnson told the Times after the visit. “It was a very good beginning.”

“More than a dozen universities have recognized their ties to slavery and the slave trade,” Swarns wrote in her June 14, 2016 article. “But historians say they believe this is the first time that the president of an elite university has met with the descendants of slaves who had labored on a college campus or were sold to benefit one.”

Fighting Racial Injustice

“We’re at this point in our history around the country, but I think particularly, at colleges and universities … where folks are having to, at last, reckon with the long effects of history,” Atlantic correspondent Ta-Nehisi Coates said in a Sept. 29 Washington Ideas Forum event with DeGioia and Harvard President Drew Faust.

Part of that reckoning resulted in DeGioia creating the Working Group on Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation, but before that group made its recommendations, he also made commitments to address the racial injustice tied to the legacy of slavery.

In February 2016, he committed to creating an African American Studies Department, recruiting new faculty and promoting scholarship in the field, establishing a center to address racial injustice and creating a working group on racial justice.

“Not for the first time, hardly, but in the past year and a half or so, we have been witness to incidents that shake our confidence in, for many, an assumption that we as a country were overcoming the legacies – and their structural groundings – of slavery, subsequent segregation and systematic racism in so much of our lives,” DeGioia said in announcing the commitments. “What we witness must lead us to confront how continual racial injustice within the American context is manifest and how to identify creative responses to it.”

The university’s board of directors approved the new department in June 2016.

The commitment to an intensified focus on racial justice gained ground when Georgetown received a five-year, $1.5 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation this past December that will assist the university in establishing a center, hiring faculty experts, supporting postdoctoral and graduate fellows and funding a series of visiting lecturers.

“The university has made a commitment to elevate and accelerate its efforts to address the persistent, enduring legacy of racism and segregation in the American experience,” Georgetown Provost Robert Groves, a co-chair of the Working Group on Racial Justice, said when the grant was announced in February 2017. “This grant from the Mellon Foundation is a notable recognition of the importance of that commitment.”

Working Together

DeGioia first visited descendants in Baton Rouge, New Orleans and Maringouin, Louisiana in late June and early July 2016.

“In our meetings with descendants, Georgetown has expressed its commitment to working with descendants and moving forward together, and even if there are points on which we don’t agree, the meetings have been cordial and supportive and constructive,” says James Benton (G’08, G’11, G’16), an alumnus who was hired last year to help organize the university’s efforts.“There may be adversarial feelings here and there. But I think people are trying to figure out how these distinct groups – the Jesuits and Georgetown and descendants – can begin to work together.”

Benton, who holds a doctorate in history from Georgetown, says he can relate to the descendants because his own genealogical research has shown his ancestors included both free people of color as well as slaves.

As part of research he did on an African American minister in his native North Carolina, he discovered that the minister’s father was a slave who was sent to another plantation nearly 200 miles away when the planter died in 1819. In reading the probate document dividing up the planter’s assets, he discovered a family of slaves that was broken up, with two of four children torn away from their parents.

“I think about that a lot, more than my own history,” Benton says. “I’m hoping people understand that there are people who are going through that same thing with the discovery of a direct ancestor and imagining what their lives were like before 1838, what their lives were like after 1838, and wondering how they and their descendants made it to emancipation, and through the 1900s during the Jim Crow era and World War I, and the Great Depression and World War II.”

Metaphor for Race Relations

Benton, Georgetown’s slavery, memory and reconciliation fellow, says some descendants have expressed pride in the survival of their ancestors while others are understandably sad or angry about what happened. But he is optimistic that Georgetown can successfully address its history of slavery.

“Whether we like it or not, the 1838 sale and how Georgetown and the descendants and the Jesuits deal with that and its aftereffects form a metaphor for race relations in our country today,” he says. “It has the potential to provide a positive counterpoint to all the discussions we have had on race in the past couple of years, which include police brutality, income inequality and other issues with the backdrop of a presidential election that had racial overtones.”

“This is happening in the context of a country that is becoming more pluralistic, where no single racial or ethnic group will hold a majority,” Benton adds. “So how do we work together? How do we build constructive solutions together? How this turns out may also be a metaphor for our capacity as a nation to face these issues.”

Forums, Teach-Ins

Conferences, forums and teach-ins on campus have complemented the visits to descendants in the past year-and-a-half, as well as presentations at conferences and other venues made by Georgetown faculty and senior leaders.

These faculty include history professors and working group members Adam Rothman, Marcia Chatelain and Maurice Jackson, as well as Jesuitgovernment professor and working group member Rev. Matthew Carnes, S.J.

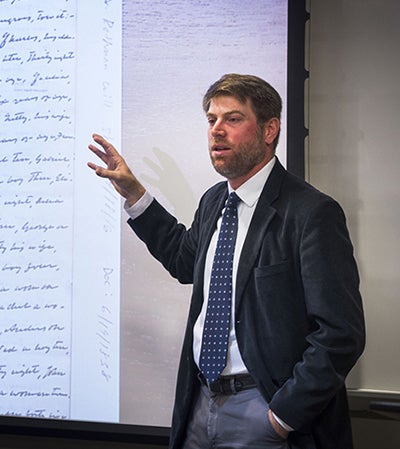

Rothman, for example, delivered a lecture in November on slavery, the Jesuits and Georgetown that took place at the National Archives and was broadcast on C-SPAN. He noted in the talk that he had accompanied some of the descendants of the 272 to Georgetown’s archives.

“One of the great joys of the work we’ve been engaged in is to get to know these people, to help them recover their family histories, to hear their perspective on what this history means to them,” he said. “I’m an academic. I write about things that happened a long time ago. … What this has done, it has collapsed the distance between the past and the present and made it all the more meaningful.”

Months of Visits, Events

In September, in addition to the Washington Ideas Forum event, Benton participated in a Homecoming panel on the topic at Georgetown and madea presentation at the College of William & Mary as part of Universities Studying Slavery, a consortium of nearly two dozen universities in the United States and Canada looking into the role slavery and issues related to race played in the development of their respective institutions.

Georgetown will be hosting the spring meeting of this consortium on campus at the end of March.

A group of nearly 45 descendants of Hicks and Butler, including Estes-Hicks and Bayonne-Johnson, traveled to Georgetown on Oct.7, visiting the campus and the Booth Family Center for Special Collections, where numerous documents related to the sale are preserved. They also attended a reception with DeGioia and other senior leaders.

“We had a tour of the Jesuit cemetery there,” says Estes-Hicks. “Then we had a tour of Georgetown, and the library put together a presentation of slave-related documents for us. President DeGioia had a nice reception for us, and we had a wonderful Mass at St. Augustine…”

Ayodele Aruleba (C’17), a student on the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation, speaks during the 2015 renaming of Mulledy and McSherry halls.

Slavery and Catholic Thought

Fall events also included Georgetown’s Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life hosting an October panel featuring Carnes, Chatelain, Benton and Diana L. Hayes, an emerita professor of systematic theology.

Ayodele Aruleba (C’17), a student on the working group, wrote a blog postabout the event.

“In light of the evidence that students in the early nineteenth century brought personal slaves to campus, just as students today would bring printers, or decorative posters to aid their transition to college life, I was reminded by Father Matthew Carnes the extent to which the forced bondage of people of African descent was recognized as a normalcy,” he wrote, “and the participants in the dreadful institution of slavery were products of their time.”

Changing Institutional Culture

When Aruleba asked at the event about how future students of the university will engage with this history, Chatelain said it’s not about just creating a statue or a memorial.

“It’s about making sure we’re in an institutional culture that reminds us to always make meaning,” she said.

As an example, she said DeGioia chose to talk about the relationship between the legacy of slavery and unrest in American cities during his introductory speech at Georgetown’s 2014 first-year convocation, which took place just weeks after the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown by a white policeman in Ferguson, Missouri.

“This changes the tone for all new Hoyas,” she said. “They are now at a school where the president of the university talks about issues of critical importance at the opening convocation, with their parents there and the faculty and the staff and this fundamentally changes the culture.”

Choosing to Remember

Marcia Chatelain

Chatelain also participated in a Slavery and Global Public History Conference at Brown University in December.

In January of 2017, the provost encouraged faculty to assign Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break the Silence,” in their courses during the spring semester and to incorporate reflections on the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation’s report.

King’s legacy was again the focus on Jan. 16, during the annual Let Freedom Ring! Concert, which included an original song commissioned by the university called”We Choose to Remember.”

The university’s archivists in the Special Collections division have regularly welcomed descendants who wish to look at the historical documents related to their ancestors.

In the Classroom

There are two courses being taught at Georgetown this semester that directly engage with Georgetown’s historical ties to slavery.

Rothman is teaching a course, American Studies 272, called Facing Georgetown’s History, in which students examine Georgetown’s roots in the Maryland Jesuits’ slave economy and its legacies.

They also contribute to the Georgetown Slavery Archive by identifying and interpreting archival materials and they develop memory and reconciliation projects related to Georgetown’s ongoing efforts. Bernard Cook, associate dean of Georgetown College and director of film and media studies, is running a Social Justice Documentary course that includes work on slavery, memory and reconciliation.

Tough Questions

Other recent events include a March 3 Harvard conference on Universities and Slavery: Bound by History at which Rothman spoke.

Rothman’s last visit to Louisiana took place with Cook and involved taking students to Louisiana, where the group visited New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Maringouin during spring break and met with descendants as well as students at Southern University and Louisiana State University.

The outreach to descendants and engagement with the history of what DeGioia has called an “evil” in 1838 and its legacy will continue over weeks, months, years and decades to come.

“If we can figure out a way to build some form of consensus, then that’s really hopeful for the future, not just for this relationship among Jesuits and enslaved people and the university, but for the nation as a whole,” Benton says. “Because we can show that it is possible and if people are willing to deal with the pain and ask the really tough questions, I think we can get there.”

Estes-Hicks, the descendant of Nace Hicks and Biby Butler, notes that “Nace” is a variant of St. Ignatius, the founder of the Jesuits.

“I think we have seven or eight Naces to this day,” she says. “It was deeply riveting to understand that the name was in the Jesuit family. My father was a Nace. My brother … is a Nace. His son is a Nace and [so] is his grandson.”

“When I think of 1838, I think of the Jesuits. I think of the priesthood,” she says. “That was always my foremost interest – simply because of my family’s deep involvement with Catholicism. My father went to sleep each night with the rosaries under his pillow.”

Members of her family recently went to see the plantation in St. Inigoes, Maryland, where some of the enslaved people lived before being sold to Louisiana plantation owners. The chapel has closed permanently but was opened for the descendants.

“Most of my family has remained Catholic, and we had this intense identification being in the chapel where our ancestors used to worship there with the Jesuits,” she says. “That was very meaningful.”