One of the hardest parts of Steven Gillen’s (G’96, ‘01) job as a hostage negotiator was telling families their loved ones weren’t coming home.

As he was getting ready to transition from his role as deputy special presidential envoy for hostage affairs (SPEHA), the last thing Gillen wanted to do was tell Paul Whelan’s family for a third time that Whelan would remain behind Russian bars. Whelan had been arrested in 2018 on trumped-up espionage charges, and Gillen had been working for three years to secure his release.

Fortunately, he didn’t need to have the same conversation again. On Aug. 1, 2024, Whelan was freed from Russia along with two other Americans, including Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, in a historic seven-nation prisoner exchange that the SPEHA team helped orchestrate.

Now, as the deputy chief of mission at the U.S. Embassy in Mogadishu, Gillen serves as the right-hand man of the U.S. ambassador to Somalia.

It’s the next phase of his career serving his country as a Foreign Service officer, a career shaped by Georgetown and Gillen’s professor and lifelong mentor.

A Formative Mentorship at Georgetown

Georgetown was Gillen’s dream school.

After graduating from Arizona State University, he pursued a master’s degree in foreign service from the School of Foreign Service (SFS) to determine how he could serve his country in international affairs.

Gillen said his Georgetown classes have been indispensable throughout his career, including at his current posting in Somalia, where he uses skills from economics, finance and security-focused courses to lead the embassy’s various teams.

Above all, he found the faculty practitioners at Georgetown — from policymakers to U.S. ambassadors — gave him invaluable mentoring. After taking the Force and Diplomacy seminar, Gillen found an especially influential mentor in his professor, Ambassador Robert Oakley.

Oakley had served as the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Somalia when he came to Georgetown to teach the seminar. In Gillen, Oakley found a rising star and nudged him early on to pursue the Foreign Service.

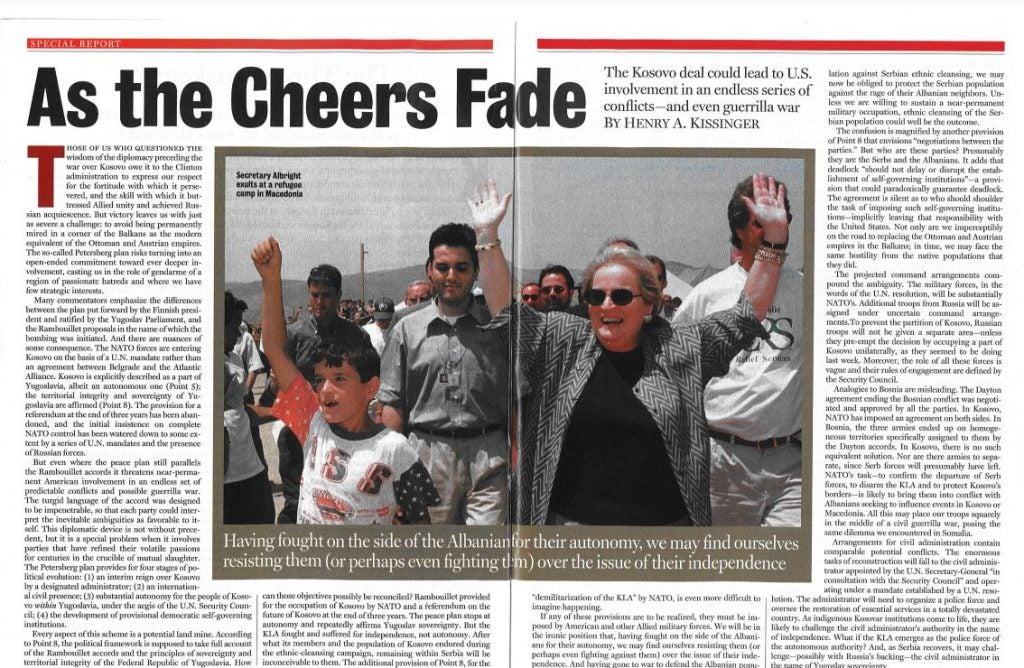

But Gillen wasn’t fully sold on following in his mentor’s footsteps. After graduating in 1996, he spent two years in North Macedonia on a Fulbright scholarship and then as a contractor with the State Department during the Kosovo War and refugee crisis. He even escorted then Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright through refugee camps in the region.

Upon returning to Washington, DC, Gillen pursued his second master’s degree in security studies at Georgetown. He also reconnected with Oakley, who never forgot about his pupil and his potential.

“Every time I encountered him, [Oakley] said, ‘You’ve got to join the Foreign Service,’” Gillen said. “I got dragged kicking and screaming into the Foreign Service, but it was the best possible move.”

In 2004, Gillen passed the Foreign Service Officer Test and joined the diplomatic corps.

Chasing the Hard Assignments

In the years following, Gillen has never shied away from challenging assignments as a diplomat.

He has served in diplomatic posts from Minsk to Sarajevo and three tours in Iraq. In back-to-back posts in Baghdad during the U.S. troop surge in 2008, he remembers coming under daily rocket attacks around the U.S. embassy.

“I know that I’m best suited to serving in places that are on the edge of breaking down, which would be devastating for the local population in terms of their human rights and quality of life and their opinion of America,” he said. “I felt like I as an individual American can make the best of my talents and make the most difference by coming to these kinds of hotspots.”

Gillen also served in multiple roles in DC, including as the deputy assistant secretary of state in the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL) and director of the Office of Near Eastern Affairs in DRL. But whenever he had the opportunity to get back into the field, he took it.

“It’s not conventional diplomacy, but it’s the sort of diplomacy my career and my heart has been attracted to. In some ways, maybe that’s why Ambassador Oakley and I hit it off,” he said. “Ambassador Oakley once joked the only non-hardship, non-danger post he ever served in was Paris, and he hated it.”

Freeing Americans From Captivity

When Gillen got the call in 2021 to be SPEHA Roger Carstens’ deputy, he decided it was the best way he could serve his country next in a challenging assignment. Negotiating for the release of Americans wrongfully detained abroad was something he had experience with and was eager to dive into again.

In a previous role in the Bureau for Near Eastern Affairs, Gillen worked on the case of Austin Tice (SFS’02, L’13), a Georgetown alumnus and American journalist who was captured in Syria in 2012. Ever since his capture, Georgetown has advocated for the release of Tice, whose mother, Debra Tice, spoke at the SFS commencement ceremony in 2023 and focused new attention on her son’s case. As deputy SPEHA, Gillen continued to work on Tice’s case and attended the 2023 commencement as his mother’s guest.

Much of Gillen’s work as deputy SPEHA involved coordinating with federal agencies, attending National Security Council meetings and devising policy options for hostage negotiations.

In his three-and-a-half-year stint, Gillen had a hand in many negotiations for Americans wrongfully detained abroad, perhaps most notably securing the release of WNBA player Brittney Griner in December 2022.

“It was a lot of ups and downs,” Gillen said. “When you get a couple of people back or somebody out of a wrongful detention or hostage situation, there are other families waiting for their loved ones to come back. Part of my job was to make that phone call [telling families,] ‘I’m really sorry we couldn’t get your loved one back this time, but we’ll keep trying.’”

In a diplomatic visit to Tel Aviv following the Oct. 7 attacks, Secretary of State Antony Blinken asked Gillen to remain in Israel to help the Israeli government in hostage negotiations and be a point of contact for the families of Americans held hostage by Hamas in Gaza.

But negotiating for the release of Whelan was always in the back of Gillen’s mind. Over the years, he had grown close with the Whelan family. In the lead-up to Whelan’s release, Gillen participated in diplomatic meetings with counterparts to support hashing out a diplomatic solution.

Gillen was packing his bags in DC to head to Mogadishu when he learned Whelan was going to be released. He was overjoyed.

“The call I ended up having with the Whelan family was much better this time. It was a nice way to cap off my time as deputy SPEHA and head off to Mogadishu.”

A Full-Circle Moment

Gillen has always wanted to serve in Somalia. In a way, Gillen is following the legacy Oakley left behind.

In the 1980s, Oakley served as the U.S. ambassador to Somalia and the special envoy for Somalia under both Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton. In his role, he led humanitarian efforts and negotiated the return of the bodies of American servicemen and the release of helicopter pilot Michael Durant, who was held captive following a battle in Mogadishu popularized by the film Black Hawk Down.

Now in similar shoes, Gillen is working on supporting Somalia’s fight against the terrorist organization Al Shabab while promoting democratization and humanitarian issues in the East African country.

For Gillen, being in Somalia is a full-circle moment.

He and Oakley remained connected up to Oakley’s passing in 2014. Gillen had completed a few overseas tours as a Foreign Service officer when he called his mentor one last time. He recalls the last words Oakley said to him, “‘Thank you, dear friend. I’m very proud of you.’”

When asked what he’d say to Oakley today, Gillen had a simple answer.

“I’d tell him he was right. This was the best possible way to serve our country, as an officer in the Foreign Service. I’d thank him for pushing me,” he said. “When I graduated from MSFS in 1996, it took about five years of him pushing me. … My Georgetown education continued even after I graduated in that regard. He saw something in me and in some ways knew more about me than I knew about myself. That’s what I’d tell him.”